Correctly classifying a crime is not an easy task.

May 13, 2022 7:14 pm

The third presentation as part of the FPA RF webinar on May 13 was, like the previous one, dedicated to answering questions from listeners who were interested in Pavel Yani’s lectures

Doctor of Law, Professor of the Department of Criminal Law and Criminology, Faculty of Law, Moscow State University. M.V. Lomonosov, member of the NCC at the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation, editor-in-chief of the magazine “Criminal Law” Pavel Yani commented on a number of practical situations in which difficulties arise with the qualification of crimes committed.

Criminal law of Russia. Special part

The concept of qualification of crimes.

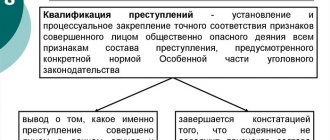

According to the approach most often found in educational and scientific literature,

the qualification of crimes

(criminal legal qualification of acts) is “the establishment and legal consolidation of an exact correspondence between the signs of the committed act and the signs of a crime provided for by the criminal law norm.”[14] This definition allows us to make two statements.

Firstly, the qualification of crimes includes two closely interrelated components: material (criminal law) and procedural (criminal procedure).

Establishing an exact correspondence (identity) between the signs (composition) of the committed act and the signs (composition) of the crime provided for by the criminal law is a material component. This is nothing more than a criminal legal assessment of a socially dangerous act, which consists in establishing the norm of criminal law to be applied.

The criminal procedural component shows that the classification of crimes has legal significance only within the framework of the process, that is, when it is given when applying a criminal law norm by an authorized official (inquirer, investigator, prosecutor, judge). The qualification of a crime as a mental process and the result of this process may exist outside the framework of the criminal process, but this will not have legal significance.

From the above we can conclude that the concept of qualification of crimes is cross-sectoral. At the same time, this does not prevent us from considering its components separately. In the course of the Special Part of Criminal Law, it makes sense to dwell first of all on the substantive and legal component of this concept. The classification of crimes is for the most part a private criminal law theory.

Secondly, the qualification of a crime as a substantive legal concept, in turn, also includes two components. On the one hand, it represents a mental process carried out according to established laws, and on the other hand, it is the result of this process, which is subsequently reflected in procedural documents.

The classification of crimes is an integral part of the application of law. Often the qualification of crimes is compared with the application of the disposition of the criminal law norm, sometimes they are even identified. Indeed, the qualification of crimes presupposes the establishment of the identity of the corpus delicti, which is provided precisely in the disposition of the criminal law norm, and the composition of the committed public act.

The concept of qualification of crimes in the doctrine of criminal law is understood more broadly than its name. The result of the “qualification of a crime” may be a conclusion about the non-criminal nature of the act (for example, due to its insignificance, the presence of circumstances excluding the criminality of the act, or due to the absence of guilt). This conclusion to a certain extent contradicts the definition of the classification of the crime. Nevertheless, extending the term “qualification of crimes” to cases of recognition of non-criminal behavior is justified. After all, initially the qualifier does not know what crime has been committed and whether a crime has been committed. Answers to these questions are given simultaneously. Probably, from a grammatical point of view, it would be more correct to use the term “criminal legal qualification of an act,” which will cover cases of recognition of both criminal and non-criminal behavior. However, the term “qualification of crimes” is well-established, and there is no particular need to look for a replacement for it.

Legal significance of classification of crimes.

The classification of crimes has criminal legal, criminal procedural, forensic and criminological significance. Let us note once again that the qualification of a crime has this meaning only if it is given when applying a criminal law norm.

The criminal legal significance of the classification of crimes is that:

1) in its process, the legal basis for the criminal liability of the person who committed a socially dangerous act is established;

2) it sets the initial limits of criminal liability;

3) the grounds for liability of persons involved in the crime are predetermined (for example, criminal liability arises for concealing only serious and especially serious crimes - Article 316 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation);

4) it influences the issues of sentencing and the application of other measures of a criminal law nature;

5) the solution to the issue of exemption from criminal liability and punishment largely depends on it.

The criminal procedural significance of the classification of crimes is that:

1) it determines the jurisdiction, jurisdiction and jurisdiction of the case;

2) it largely sets the grounds for removing the guilty person from his position for the period of investigative actions;

3) incorrect qualification is the basis for returning the criminal case to the inquiry officer or investigator.

The forensic significance of the classification of crimes is manifested in the fact that it largely predetermines the issues of organizational interaction between various bodies.

Finally, the criminological significance of the classification of crimes is that it is an important accounting statistical indicator of crime.

Types of qualification of crimes.

The classification of a crime, depending on who gives it, can be official (legal) or unofficial. The official one comes from the competent state bodies when applying criminal law, is reflected in procedural documents (resolution to initiate a criminal case, court verdict, etc.) and entails legally significant consequences. Unofficial qualifications do not have binding force. Among all the varieties of unofficial qualifications, it is necessary to highlight the doctrinal qualifications given by scientists in connection with theoretical searches, scientific analysis of law, as well as as a result of such searches and analysis.

Classification of crimes as a thought process.

The thought process for establishing the criminal law to be applied includes three components:

1) interpretation of the law (clarification of its meaning), with the help of which many elements of acts prohibited by criminal law are determined; the meaning of the law is established through grammatical and systematic methods;

2) interpretation of the act, which is the establishment of legally significant features of the act; of all the signs of the crime, only those that are significant when applying the criminal law are highlighted;

3) search for a norm based on a comparison of many legally significant signs of an act, established through the interpretation of the act, and the elements of crimes established as a result of the interpretation of the criminal law.

Qualification of crimes in procedural documents.

Reflection of the classification of a crime in procedural documents requires compliance with certain formalities. Qualifying an act as a crime requires mandatory indication of the norm (article, and, if necessary, part of the article and paragraph) of the Special Part of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. In relation to a specific socially dangerous act, one cannot talk about a crime in general; it is required to indicate what type of crime was committed (theft, murder, or other). So, if a murder is committed without mitigating and aggravating circumstances, then it is qualified under Part 1 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code. Kidnapping of a person for mercenary reasons requires qualification under paragraph “h” of Part 2 of Art. 126 of the Criminal Code.

The law does not regulate the order in which, when qualifying a crime, the article number, the number of the part of the article and the paragraph must be indicated. In our opinion, it is logical to arrange the components of a criminal law norm “from least to greatest,” that is, first indicate the paragraph(s), then the part and at the end the number of the article of the Special Part. However, recently in practice they use a different sequence - “from largest to smallest”: first the number of the article of the Special Part of the Criminal Code is given, then the number of the part of the article and the paragraphs. By indicating at the beginning of the so-called letter classification of a crime the number of the article of the Special Part, we thereby immediately determine the type of crime committed (if Art. 105 - then murder, if Art. 162 - then robbery, etc.).

One crime can be qualified only under one part of the article of the Special Part of the Criminal Code. For example, if a theft is committed with illegal entry into a home by a group of persons by prior conspiracy, the act will be qualified only under Part 3 of Art. 158 of the Criminal Code, despite the fact that there is another legally significant feature provided for in paragraph “a” of Part 2 of Art. 158 of the Criminal Code - committing theft by a group of persons by prior conspiracy. The norms provided for in parts 2 and 3 of Art. 158 of the Criminal Code, compete with each other. Therefore, only a special norm is required. We will talk in more detail about the rules for classifying crimes in competition between criminal law norms below. At the same time, the descriptive part of the indictment or court sentence must indicate all legally significant circumstances. The commission of theft by a group of persons by prior conspiracy is not indicated in the letter qualification, but is given in the descriptive part of the document, and therefore must be taken into account when assigning punishment as a circumstance affecting the nature and degree of social danger of the act.

If there are several aggravating circumstances provided for by several paragraphs of the same part of the article, all relevant paragraphs are indicated in the qualification. For example, if a robbery is committed by an organized group in order to seize property on a particularly large scale with the infliction of grievous harm to the health of the victim, then the act requires qualification under paragraphs “a”, “b”, “c” of Part 4 of Art. 162 of the Criminal Code.

In addition to indicating the norm of the Special Part, in two cases, when qualifying a crime, a reference to the General Part is required.

If an unfinished crime has been committed, then a reference to the relevant part of Art. 30 CC. Thus, preparation for murder is qualified under Part 1 of Art. 30 of the Criminal Code and the corresponding part of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code. Attempted simple robbery is qualified under Part 3 of Art. 30 of the Criminal Code and the corresponding part of Art. 161 CC. The need to refer to the norm of the General Part is directly stated in Part 3 of Art. 29 of the Criminal Code: “Criminal liability for an unfinished crime occurs under the article of this Code, which provides for liability for a completed crime, with reference to Art. 30 of this Code."

Reference to the General Part is also required to qualify the actions of an accomplice who is not the perpetrator of the crime. In Part 3 of Art. 34 of the Criminal Code stipulates that the criminal liability of the organizer, instigator and accomplice arises under the article providing for punishment for the crime committed, with reference to Art. 33 of the Criminal Code, except for cases where they were simultaneously co-perpetrators of the crime. Thus, the actions of an accomplice to robbery will be qualified under Part 5 of Art. 33 and the corresponding part of Art. 162 of the Criminal Code. The organizer of the murder will be held liable under Part 3 of Art. 33 and art. 105 of the Criminal Code. If the organizer of the murder simultaneously also acts as a co-perpetrator of the crime, then his actions are qualified only under Art. 105 of the Criminal Code. However, the fact of organizing a crime must be reflected in the descriptive part of the procedural document and will subsequently be taken into account when assigning punishment. Link to Art. 33 of the Criminal Code is not needed here. If a person is both an instigator and an accomplice, then it is necessary to refer simultaneously to both Part 4 and Part 5 of Art. 33 of the Criminal Code.

Of particular interest are cases when an accomplice, instigator or organizer of the crime is brought to justice for an unfinished crime. In accordance with the literal meaning of the criminal law, in this situation a reference to Art. 30, and at st. 33 of the Criminal Code. For example, if the organizer of a murder is brought to justice, which was interrupted at the stage of an attempted crime, then the act is qualified under Part 3 of Art. 30, part 3 art. 33 and art. 105 of the Criminal Code. Sometimes, in case of an unfinished crime, in practice they do not refer to Art. 33 of the Criminal Code, which contradicts the meaning of the law. Link to Art. 33 of the Criminal Code is needed in the case of both completed and unfinished crimes.

The qualification of a crime has its own specificity under the blanket disposition of an article of the criminal law, when the Criminal Code refers to a normative act of a different branch to establish the illegality of an act. Here, along with the letter qualification, it is also necessary to indicate which norms of another industry affiliation were violated by the crime committed. Thus, in paragraph 1 of the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation dated April 26, 2007 No. 14 “On the practice of courts considering criminal cases of violation of copyright, related, inventive and patent rights, as well as illegal use of a trademark”[15] states, that when deciding whether a person is guilty of committing a crime under Art. 146 of the Criminal Code, the court must establish the fact of violation by this person of copyright or related rights and indicate in the verdict which right of the author or other copyright holder, protected by which particular norm of the law of the Russian Federation, was violated as a result of the crime.

Solving the problem of finding a violated norm of another industry and, accordingly, referring to it does not cause much difficulty in the case when in a normative act of another industry, to which the criminal law refers, the required norm is formulated in the form of an administrative order. Thus, the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation in paragraph 3 of Resolution No. 25 of December 9, 2008 “On judicial practice in cases of crimes related to violation of traffic rules and operation of vehicles, as well as their unlawful taking without the purpose of theft”[ 16] indicates that when considering cases of crimes under Art. 264 of the Criminal Code, courts should indicate in the verdict which specific paragraphs of the Traffic Rules or vehicle operating rules were violated that resulted in the consequences specified in Art. 264 of the Criminal Code, and what exactly this violation was expressed in. Traffic rules are, in computer parlance, a menu of administrative regulations.

It is another matter if such a prescription is not formulated as a separate norm, but follows from several provisions or even from the meaning of the law. In this situation, one should proceed from the principle of necessity and sufficiency of reference. On the one hand, it is required to indicate the rules that provide for the corresponding violated rule, on the other hand, cluttering procedural documents with unnecessary information cannot be justified. So, in the case of committing a crime under Part 2 of Art. 146 of the Criminal Code, expressed in the illegal use of copyright objects in the form of illegal distribution of counterfeit copies of works, the exclusive right to the work, which is regulated by Art. 1229 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation. Therefore, a link to this article is required. The question is whether, in addition to Art. 1229 of the Civil Code refer to other articles of the Civil Code regulating the circulation of exclusive rights. The correct answer seems to be negative. Link to Art. 1229 of the Civil Code already sufficiently ensures the qualification of the crime.

Principles of qualification of crimes.

The classification of crimes must meet a number of principles. In the theory of criminal law, the question of the number of principles and their content is debatable. Nevertheless, almost all researchers consider accuracy and completeness to be the principles of qualification.

The accuracy of the classification of a crime means the establishment of exactly that criminal law norm that contains the signs of the incriminated act. You cannot qualify “with a reserve” or “with a deficiency.” Overqualification or “qualification with reserve”, when attributes are imputed that actually do not exist or the presence of which is very doubtful, is sometimes given by the investigation and the prosecution for insurance, so that there is an “item of trade” with the defense. Such qualifications are not accurate and are therefore illegal. Also illegal is under-qualification, “qualification with a deficiency”, when certain characteristics that actually occur are not taken into account.

Crimes cannot be imputed alternatively. For example, a typical mistake in classifying fraud is to impute to the guilty person theft committed by deception or

abuse of trust. With such qualifications there is an element of fortune telling. The accusation is not properly specified. The law provides that fraud may be committed either by deception, by breach of trust, or by deception and breach of trust. There is no fourth option.

Completeness of qualification involves indicating all articles and points that formulate the crimes committed by the perpetrator. This applies, first of all, to an ideal totality, when several crimes are committed by one act. Here, when qualifying what has been done, some crimes can be overlooked. For example, if a person illegally transports drugs across the customs border, then he commits at least two crimes. The first is provided for in Art. 2291 of the Criminal Code, second - Art. 228 CC.

The completeness of the qualification of a crime requires the indication of all the signs of the crime committed with an alternative structure of the crime. Thus, if a person first acquired a narcotic drug for his own consumption, and then stored and transported it, then it should be indicated that the culprit committed three types of socially dangerous actions provided for in Art. 228 of the Criminal Code (purchase, storage and transportation of narcotic drugs).

The completeness of the qualification of a crime also involves indicating the mandatory elements of the crime committed. First of all, this concerns signs of guilt. So, if a murder is committed, then it is required to indicate with what intent (direct or indirect) the death was caused, as well as to disclose the content of guilt.

When qualifying a crime, it is also necessary to take into account the provisions arising from the principles of the Criminal Code:

— subjective imputation

; according to Art. 5 of the Criminal Code (“Principle of Guilt”), a person is subject to criminal liability only for those socially dangerous actions (inaction) and socially dangerous consequences that have occurred in respect of which his guilt has been established; criminal liability for innocent causing of harm is not permitted;

— inadmissibility of double qualification

; in accordance with Part 2 of Art. 6 of the Criminal Code no one can be held criminally liable twice for the same crime; this provision is interpreted in the doctrine wider than its literal meaning; It is impossible not only to impute the same crime repeatedly, but also to impute the same legally significant circumstances several times.

It is also necessary to be guided by the principle of interpretation of unresolved doubts in favor of the person whose act is qualified (based on well-known constitutional and procedural provisions). The Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation in paragraph 4 of Resolution No. 1 of April 29, 1996 “On the Judicial Sentence”[17] explained that, within the meaning of the law, not only irremovable doubts about his guilt in general, but also irremovable doubts, are interpreted in favor of the defendant. concerning individual episodes of the charge, the form of guilt, the degree and nature of participation in the commission of a crime, mitigating and aggravating circumstances, etc. The same should be done when there are unresolved doubts about the interpretation of the law.

The classification of a crime is always determined by the actual circumstances of the crime. Therefore, for correct qualification, complete information about the crime committed is required. Often, the results of the classification of a crime given at different stages of the criminal process differ significantly: when a criminal case is initiated, one qualification, and when an accusation is brought, another. This is, as a rule, not due to the qualifier’s errors, but to the fact that the qualification is based on different factual information. For example, a criminal case is initiated under Part 1 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code, during the investigation a hooligan motive is established, and charges are brought under paragraph “i” of Part 2 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code.

Qualification of crimes in the competition of criminal law norms.

The competition of criminal law norms is a contradiction that can be resolved through a systematic interpretation of the criminal law. A. A. Gertzenzon defined competition as “the presence of two or more criminal laws that equally provide for the punishability of a given act.”[18] Thus, the prescription of Part 1 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code competes with the norms provided for in Part 2 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code. Prescriptions Art. 105 of the Criminal Code compete with the norms provided for in Art. 106–108 CC. The grammatical conflict of the specified criminal law norms is resolved by systemic means.

In the theory of criminal law, there is competition between general and special norms, competition between parts and the whole.

When there is competition between a general and a special norm, the latter (special) provides for a special case of an act specified in the general norm. So, according to the grammatical meaning of Part 1 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code covers all cases of intentional causing the death of another person. At the same time, in Art. 317 of the Criminal Code provides for liability for an attempt on the life of a law enforcement officer, which is a special case of murder. According to Part 3 of Art. 17 of the Criminal Code, if a crime is provided for by general and special norms, there is no totality of crimes and criminal liability arises according to the special norm.

When a part and a whole compete, one norm (part) provides for liability for an act that is part of another act, the responsibility for which is provided for in another norm (the whole). As part and whole, the norms on causing grievous harm to health (Article 111 of the Criminal Code) and robbery with causing grievous harm to health (clause “c” of Part 4 of Article 162 of the Criminal Code) correlate. When there is competition between the part and the whole, the act is qualified according to the norm (the whole), since it covers all the legally significant features of the act. If during the robbery grievous harm is caused to the health of the victim, then the attack is qualified under paragraph “c” of Part 4 of Art. 162 of the Criminal Code, which covers the occurrence of consequences in the form of serious harm to health, therefore additional qualifications under Art. 111 of the Criminal Code is not required.

In Part 1 of Art. 17 of the Criminal Code stipulates that the commission of two or more crimes is recognized as a set of crimes, for none of which the person was convicted, except for cases where the commission of two or more crimes is provided for by the articles of the Special Part of the Criminal Code as a circumstance entailing a more severe punishment. This prescription only partially reproduces the rule of qualification in competition between the part and the whole.

In the doctrine, the question of the advisability of separating part-whole competition into a separate type is debatable. The fact is that the identification of several types of phenomena within one classification should be based on one criterion. The identification of competition between the part and the whole is based on the logical relationship between the volume and content of competing laws. At the same time, norms that compete as general and special also have this property. So, the norm of Part 1 of Art. 158 of the Criminal Code is part of the norm provided for in paragraph “a” of Part 2 of Art. 158 of the Criminal Code. It would seem that there is competition between the part and the whole, however, as a rule, they say that these norms are in the ratio of general and special. General and special norms are usually found in the relationship between the part and the whole.

In connection with the above, it is fair to say that it is inappropriate to distinguish such a type of competition as competition between the part and the whole. Another thing is that the recognition of competing norms and the construction of corresponding rules for classifying crimes is easier to explain based precisely on the formal-logical relationship of these norms.

Special norms are often formed by identifying qualifying and privileged characteristics. The corresponding norms are called qualified (with aggravating circumstances) and privileged (with mitigating circumstances). Theory and practice have developed the following rules for qualifying crimes provided for by these norms:

1) in case of competition between the main and qualified norms, the qualified one is subject to application;

2) in case of competition between the main and privileged norms, the privileged one is subject to application (for example, in case of competition, Part 1 of Article 105 and Part 1 of Article 108 of the Criminal Code, Part 1 of Article 108 of the Criminal Code is applied);

3) when there is competition between two qualified norms, the most qualified one is subject to application, i.e., one that provides for stricter liability (for example, when there is competition in paragraph “a” of Part 2 of Article 158 and Part 3 of Article 158 of the Criminal Code, Part 3 of Art. 158 CC);

4) when there is competition between two privileged norms, the most privileged one is subject to application, i.e., the one providing for less strict liability (for example, in the case of competition between Article 107 and Part 1 of Article 108 of the Criminal Code, Part 1 of Article 108 of the Criminal Code is applied);

5) when there is competition between a qualified and a privileged norm, the privileged one is subject to application (for example, the murder of two persons when the limits of necessary defense are exceeded will be qualified under Part 1 of Article 108, and not under paragraph “a” of Part 2 of Article 105 of the Criminal Code).

The most difficult practical problem of classifying crimes in the presence of competition of norms is related to the recognition of competing norms. If it is established that the norms are in a state of competition, then, with rare exceptions, no questions arise when choosing one of them. Today, the recognition of competing norms is largely based not on the rules formally expressed in the law, but on the provisions of the doctrine of criminal law, in which, alas, not all issues are resolved unambiguously. For example, in theory, the question arises about the qualification of theft committed by the head of an enterprise and resulting in non-payment of wages to employees. The offense contains signs of crimes under Art. 1451 (“Non-payment of wages, pensions, scholarships, benefits and other payments”), 160 (“Misappropriation or embezzlement”) of the Criminal Code. In this situation, is it necessary to charge two crimes or is it enough to limit ourselves to one theft? In theory, one can find various approaches to solving this problem.

The question of the classification of murders associated with the commission of other crimes (robbery, rape, etc.) is controversial. This issue at the level of clarifications of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation is resolved in favor of the absence of competition between these regulations. For example, in paragraph 13 of the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation dated January 27, 1999 No. 1 “On judicial practice in cases of murder (Article 105 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation)”[19] provides: “Under murder associated with rape or violent acts of a sexual nature should be understood as murder in the process of committing these crimes or for the purpose of concealing them, as well as committed, for example, for reasons of revenge for resistance provided during the commission of these crimes. Considering that in this case two independent crimes are committed, the crime should be qualified under paragraph “k” of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code and, depending on the specific circumstances of the case, according to the relevant parts of Art. 131 or Art. 132 of the Criminal Code." Thus, the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation considered that the norms provided for in paragraph “k” of Part 2 of Art. 105 and art. 131 and 132 of the Criminal Code do not compete with each other (they are not special and general). This approach to the qualification of acts containing elements of several crimes has been repeatedly criticized.

At the same time, a different approach to assessing murders associated with the commission of other crimes was also known in practice. Thus, the Supreme Court of Chuvashia found I. guilty of murder involving rape and qualified the act under clause “e” of Art. 102 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR, excluding Art. 117 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR, referred to the fact that “rape does not form an independent element, but is only a qualifying feature and is covered by the disposition of clause “e” of Art. 102 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR.”[20]

Qualification of crimes when changing legislation.

When qualifying a crime, it is important to take into account the rules of operation of the criminal law in time, or more precisely, the possibility of applying the retroactive force of the criminal law (Article 10 of the Criminal Code) if changes have been made to the law since the commission of the crime. If a crime was committed during the operation of the old law, then, as a general rule, it will be classified under the old law. If, according to the new law, an act has been decriminalized or depenalized, then the act requires qualification under the new law.

The qualification of a crime when changing regulations of another industry deserves a separate discussion.

Analysis of scientific works, legislation, intersectoral connections of criminal law and law enforcement practice allows us to identify the following main cases when changes in regulations of other industries allow the use of retroactive force of the criminal law when classifying crimes:

1) purposeful transfer of acts recognized as crimes to the category of administrative torts or other offenses. In Art. 7.27 of the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses (hereinafter referred to as the Administrative Offenses Code) provides for administrative liability for petty theft of someone else’s property through theft, fraud, misappropriation or embezzlement in the absence of signs of crimes provided for in Parts 2–4 of Art. 158, part 2–3 art. 159, part 2–3 art. 160 CC. At the same time, the note to this article of the Code of Administrative Offenses stipulates that the theft of someone else’s property is considered petty if the value of the stolen property does not exceed 1000 rubles. If the note increases the amount of petty theft, this will lead to partial decriminalization and create the need to apply the retroactive force of the criminal law;

2) lifting the ban on certain actions, as a result of which an act previously recognized as a crime becomes not subject to any liability at all. For example, in paragraph 17 of the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation dated November 18, 2004 No. 23 “On judicial practice in cases of illegal entrepreneurship and legalization (laundering) of funds or other property acquired by criminal means”[21] provides: “If Federal legislation excludes the corresponding type of activity from the list of types of activities, the implementation of which is permitted only on the basis of a special permit (license); in the actions of a person who was engaged in this type of business activity, there is no corpus delicti under Art. 171 of the Criminal Code." This means that a change in the law of another industry entails the termination of criminal prosecution in connection with the decriminalization of the act;

3) cases when the new law provides for the retroactive application of a law in another industry. So, in paragraph 4 of Art. 5 of the Tax Code of the Russian Federation provides that acts of legislation on taxes and fees that abolish taxes and/or fees, reduce tax rates (fees), eliminate the obligation of taxpayers, payers of fees, tax agents, their representatives or otherwise improve their situation may have retroactive effect if expressly provided for. Taking into account this legal provision, the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation o.[22]

A study of the practice of applying criminal legislation shows that changes in regulations of other industries can influence the application of retroactive force of the Criminal Code indirectly, through the constituent features included in the disposition of the criminal law norm. There is a known case of reclassification of an offense under paragraph “k” of Part 2 of Art. 105 on part 1 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code in connection with the decriminalization of the act for the commission of which or in order to conceal which the murder was committed.[23] The disposition provided for in paragraph “k” of Part 2 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code, is not blanket. There is no explicit or hidden reference to a normative act of another industry. However, indirectly, through the sign of “crime” used by the legislator,[24] it formally becomes possible to take into account changes in the regulations of other industries, if criminal liability for the corresponding crime can be abolished or mitigated by amending the law of another industry. Although this use of the Criminal Code has caused mixed assessments among specialists, it nevertheless has a certain basis. Indeed, in paragraph “k” of Part 2 of Art. 105 of the Criminal Code provides for liability for murder in order to conceal or facilitate the commission of another crime, and not an administrative tort. Meanwhile, if the corresponding act ceases to be criminal, then it can be questioned that the murder was committed with the aim of committing a crime or in order to hide it.

Dalida A.Yu. Rules for the qualification of crimes when changing the criminal law

The youth. Education. Society: materials of the International Scientific and Production Complex (Irkutsk, May 02, 2022)

Rules for the qualification of crimes when changing the criminal law

Rules for the qualification of crimes when the criminal law is amended

| Dalida Alena Yurievna Dalida Alena Yuryevna Master's student of the All-Russian Federation Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education RGUP, Irkutsk |

Annotation. The article examines the opinions of scientists regarding the concept, characteristics and meaning of the qualification of a crime when changing the criminal law. Based on this study, rules for qualifying a crime when changing the criminal law are formulated.

Annotation. The article examines the opinions of scientists regarding the concept, signs and significance of the qualification of a crime when a criminal law changes. Based on this study, the rules for the qualification of a crime are formulated when the criminal law is amended.

Key words: criminal law, qualification, criminal law, crime, qualification rules.

Key words: criminal law, qualification, criminal law, crime, rules of qualification.

The correct classification of crimes, as is known, is of utmost importance in the light of the implementation of the principles of legality, justice, personal responsibility for culpable harm, and also ensures an effective impact on crime on the part of the state, affirms a sense of security in society. Often these essential provisions are violated at various stages of criminal proceedings.

At first glance, the task of correctly classifying crimes should be solved without any restrictions at any stage of criminal proceedings. At least there are no criminal legal restrictions for this. Moreover, the principle of legality requires precise and strict compliance with criminal law by any subject of law enforcement.

The classification of crimes as a dynamic process of establishing the identity of the signs of an actually committed act with the elements of a crime has certain specifics at each stage of the criminal process and is enshrined in criminal procedural documents drawn up by employees of the investigation, prosecutor's office and court. The classification of a crime is carried out at all stages of the investigation and trial of a criminal case. At each of them, a legal assessment of the act is given, the corpus delicti containing the elements of the act, and the norm of the criminal law providing for liability for this act are determined.

Qualification (from the Latin qualis - quality, facere - to do) means the characteristics of an object, phenomenon, the attribution of a phenomenon according to its qualitative characteristics, properties to any groups, categories, classes.

In the domestic legal literature, many definitions of the classification of crimes are given, rules for qualification and rules for changing the classification of crimes are proposed. For the first time, the definition of qualification was given by V.N. Kudryavtsev in 1971 and defined this concept as the establishment and legal consolidation of an exact correspondence between the signs of an act committed and the signs of a crime provided for by a criminal law norm. [1]

So, for example, A.V. Korneeva defines the qualification of crimes as a logical process of establishing the elements of a crime in socially dangerous behavior of a person and the result of this process, that is, fixing in procedural documents a reference to the criminal law to be applied. [2]

N.K. Semernyova, speaking about the qualification of crimes, defines it as a criminal legal assessment of a specific socially dangerous act, establishing the correspondence of the signs of the committed act with the signs of the crime provided for by a specific article of the criminal law. The purpose of qualification is to establish this conformity. [3]

According to the author, the most complete and accurate definition of the concept of “qualification” was given by A.V. Korneeva, since it contains all its essential features.

Qualification is not only the result of a certain activity, but also a process during which the circumstances of a particular act are compared with the features of a legal norm, individual provisions of the law are clarified, new facts are established, versions are changed and a path for further research is outlined.

The mental logical activity of a law enforcement officer who classifies a crime, on the way to solving the final problem, goes through several stages, the totality of which is called the qualification process.

The first stage in this process is to isolate from the variety of factual circumstances established in a criminal case those that have criminal legal significance and systematize them.

The second stage of the process of qualifying a crime is to determine all possible constructions of elements of a crime that can and should be “ tried on” to the actual circumstances of the case established at the moment of the proceedings. As a result of this activity, the range of legal norms is narrowed, at least within the section, chapter of the criminal code, reflecting the generic or specific objects of crimes, when it can be said that a crime has been committed against a person, property, management order, etc.

The third stage of the process of qualifying a crime is to identify a group of all related offenses that may be relevant to a given case. So, if a police officer is killed as a result of a collision with a car, the one in whose proceedings the criminal case is pending can focus on “trying on” the actual circumstances of the case from the position of part 3 of Article 264 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) (violation of traffic rules resulting in the death of a person through negligence), Article 105 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (murder) and Article 317 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (attack on the life of a law enforcement officer). According to this alternative, planning is carried out to establish the missing characteristics.

The fourth and final stage of the process of qualifying a crime is the selection of one composition that corresponds to the crime according to all objective and subjective criteria. [4]

According to Part 1 of Article 9 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, a socially dangerous act is qualified under the article of the criminal law that was in force at the time the act was committed. In this regard, the question of what is meant by the time of commission of the crime requires clarification. In accordance with Part 2 of Art. 9 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the time of commission of a socially dangerous action (inaction) is recognized as such, regardless of the time of the onset of consequences. Article 10 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation contains an exception to the general rule that a socially dangerous act is qualified under the article of the criminal law that was in force at the time the act was committed: a criminal law that eliminates the criminality of the act, mitigates punishment or otherwise improves the situation of the person who committed the crime, has retroactive effect, i.e. it applies to persons who committed a socially dangerous act before such a law came into force, including persons serving a sentence or who have served a sentence but have a criminal record. In this case, it is possible to reclassify the person’s offense in accordance with the new law. [5]

So, the rules for classifying crimes when changing the criminal law are as follows.

- Socially dangerous acts are classified under the article of the criminal law that was in force at the time the act was committed (Part 1 of Article 9 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation).

- If a new criminal law removes the criminality of an act committed by the perpetrator, it cannot be classified as a crime.

- If a new criminal law does not completely eliminate the criminality of an act, but changes the rules for its qualification, then if it mitigates the punishment, the act is subject to reclassification under the corresponding article of the new law. If the punishment is increased, it is qualified under an article of the old criminal law.

- If a new criminal law mitigates the punishment or otherwise improves the situation of a person, it has retroactive effect, and the acts committed by the person are subject to reclassification under the new law.

- If the disposition of the norm of the new criminal law is narrower in terms of the range of acts described, the person’s actions may lack the elements of a crime or the act may be subject to reclassification under an article of the law containing a more lenient sanction.

- If the disposition of the norm of the new law is broader and the sanction is milder, the norm has retroactive effect in relation to acts that are criminal in accordance with both the old and the new law.

- If the disposition and sanction of a norm of the new law coincides with the disposition and sanction of a norm of the old law, qualification is made according to the law in force at the time the crime was committed (Part 1 of Article 9 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation).

- If the disposition of the norm of the new law is broader, this norm does not have retroactive effect in relation to acts characterized by new characteristics.

- If a new criminal law increases the punishability of an act without changing the disposition of the norms of the old law, it does not have retroactive effect (Part 1 of Article 10 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation).

- If the intermediate law is more lenient than the law in force at the time the crime was committed, the classification is made according to the intermediate law.[6].

List of sources:

- Korneeva A.V. Theory of qualification of crimes: a textbook for undergraduates. – Moscow: Prospekt, 2016. P. 55.

- Kudryavtsev V.N. General theory of classification of crimes. M., 2013. 18-20.

- Mozyakov V.V. Guide for investigators / Ed. ed. V.V. Mozyakova. M.: Exam, 2013. 10-11.

- Rarog A.I. Qualification of crimes based on subjective characteristics. SPb., 2013.C. 96.

- Savelyeva V.S. Fundamentals of qualification of crimes: Textbook. "Prospect", 2014. pp. 24-30.

Semernyova N.K. Qualification of crimes (general and special parts). Scientific and practical manual. – Prospekt LLC, 2014. pp. 8-11.

The Constitutional Court examined the issue of qualification of the same act under different provisions of the Criminal Code

The Constitutional Court published Resolution No. 1374-O of July 9, by which it terminated the proceedings on the case of checking the constitutionality at the request of the Ryazan District Court of the provisions of the Criminal Code, which allow qualifying purchases with payment for goods (services) in non-cash form with someone else's bank card under several articles .

The court in Ryazan doubted the constitutionality of the provisions of the Criminal Code

In September 2022, citizen P. was charged with committing a crime under Part 1 of Art. 159.3 “Fraud using electronic means of payment” of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. According to the indictment, using a found bank card in the name of citizen T. and acting for selfish reasons, P. made contactless payments for several goods and services totaling more than 4 thousand rubles, causing material damage to the victim.

The Deputy Prosecutor of the Zheleznodorozhny District of Ryazan, having examined the materials of the criminal case, came to the conclusion that it was necessary to qualify the act of the accused under paragraph “g” of Part 3 of Art. 158 “Theft” of the Criminal Code and decided to send the criminal case for preliminary investigation. As a result, citizen P. was charged with a new charge of stealing someone else’s property from a bank account (in the absence of signs of a crime under Article 159.3 of the Criminal Code).

The criminal case was received by the Zheleznodorozhny District Court of Ryazan, but it suspended the proceedings and, by a resolution dated February 17, 2022, decided to send the request to the Constitutional Court.

The Zheleznodorozhny District Court asked the Constitutional Court to check whether the provisions of paragraph “g” of Part 3 of Art. 158 and art. 159.3 of the Criminal Code of the Constitution of the Russian Federation to the extent that, taking into account the existing law enforcement practice, they allow the same actions to be qualified as under paragraph “g” of Part 3 of Art. 158, and under Art. 159.3 of the Code. According to the district court, the qualification of the same act under different provisions of the Criminal Code violates the principles of equality and legal certainty. This uncertainty, the request stated, violates the principle of justice: the same damage is assessed as a sign of either a serious crime, a crime of minor gravity or an administrative offense.

The Constitutional Court analyzed the controversial norms

Having considered the case materials, the Constitutional Court recalled that the Constitution entrusts the federal legislator with the establishment of measures aimed at protecting property from criminal attacks, obliging him to be guided by the principles of legal equality and legal certainty, which are described in Art. 19 (part 1) and 54 (part 2) of the Constitution (Resolution of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation of December 11, 2014 No. 32-P).

The Constitutional Court indicated that, according to paragraph 1 of the notes to Art. 158 of the Criminal Code, theft is understood as the illegal gratuitous seizure and (or) circulation of someone else's property for the benefit of the perpetrator or other persons, committed for personal gain and causing damage to the owner or other holder of this property. This concept applies to all types of theft provided for by the Code, including theft and fraud. “Thus, within the meaning of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, theft and fraud are independent types (forms) of theft, and in relation to each other they form related crimes, the main criterion for distinguishing them is the method of committing such acts,” the definition states.

At the same time, the Constitutional Court drew attention to the fact that since the special signs of theft of funds from a bank account and fraud committed using electronic means of payment are not defined in the said criminal law, the content of such signs must be established through the norms of a different industry. Thus, in order to properly differentiate the elements of the relevant crimes, rules are needed that define, in particular, the concept of a bank account, electronic means of payment, and the procedure for their use for non-cash payments.

At the same time, the Court recalled its repeatedly expressed position that the assessment of the degree of certainty of the concepts contained in the law should be carried out based not only on the text of the law itself, the wording used, but also on their place in the system of normative regulations. Regulatory norms that directly establish certain rules of behavior do not necessarily have to be contained in the same normative legal act as the norms establishing legal liability for their violation (resolutions No. 9-P dated May 27, 2003; February 14, 2013 No. 4-P; dated June 17, 2014 No. 18-P, etc.).