Legal and factual errors: types, characteristics and criminal legal significance

The occurrence of a more serious consequence than the subject intended excludes liability for its intentional infliction.

In cases where the infliction of a more serious consequence was covered by careless fault, the person, along with responsibility for the intentional infliction (or attempt to inflict) the intended consequence, is also liable for the careless infliction of a more serious consequences, if provided by law. There are two possible qualification options

An act is qualified according to one criminal law norm if it, while establishing liability for the intentional infliction of some consequences, provides for careless infliction of more serious consequences as a qualifying feature (Part 2 of Article 167, Part 4 of Article 111 of the Criminal Code). If there is no such rule in the Criminal Code (for example, about abuse of power, which through negligence resulted in the death of the victim), as well as in cases of a real set of crimes (trying to intentionally cause serious harm to the health of one person, the perpetrator through negligence causes the death of another person), the act must be qualified under the articles of the Criminal Code on the intentional infliction (or attempted infliction) of the intended consequence (Part 1 of Article 111 of the Criminal Code) and on the careless infliction of a more serious consequence that actually occurred (Article 109 of the Criminal Code).

Factual error

This classification of errors includes a person’s incorrect assessment of the actual content of signs representing the subject and objective side of criminal actions. It is divided into essential and non-essential. If the error is significant (legally significant signs of a crime), the nature of the act and the measure of responsibility for the actions taken are adjusted.

Such errors include:

- Error in the object of encroachment. The object in relation to which the damage was caused is mistakenly recognized by the culprit as the target of criminal actions, but in fact it is different from the one that is the motivation for the crime. For example: a criminal entered a pharmacy store to steal medications containing a narcotic component. I didn’t have a table of medications. He made a mistake and actually stole a different drug. When qualifying this crime, it is taken into account that it was completed, and the intent indicates an attempt on narcotic drugs. Thus, a person is subject to criminal liability specifically for attempted theft of medicines containing drugs. When these errors are discovered, qualification is carried out for each case individually.

- Incorrect identification of the victim. The subject of the error is causing harm to a person who is not a predetermined victim of the crime. Such an error does not amend the culpability and qualifications of the crime if the alleged victim does not belong to the category of special characteristics of the crime. For example: a private person received injuries incompatible with life, and the intention was to commit a crime against a government official in order to terminate the exercise of his powers.

- Choosing a means for a criminal act. The essence of the error is the use of a crime other than the planned method or object of its commission. When criminally qualifying, it is taken into account whether the crime was committed by “insignificant means” (prayers and rituals were used for murder) or whether the subject of the crime was replaced (a kitchen knife with a dagger).

- Causal relationship. To qualify a crime, the criminal’s awareness of the connection between his action (for example, stabbing a person) and the onset of consequences (the death of the victim) is insignificant. An error can only be taken into account if the offender has mental disorders, established in a certain legal way.

Currently, the country's criminal legislation does not have sections establishing the definition and significant role of error.

But the discussion of criminal legislation and work on amendments also concerns the possibility of including these provisions in the future.

Introduction

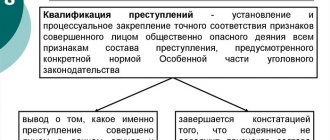

In the process of investigating criminal cases, the qualification of the crime is of great importance. Only after the act is qualified and classified as a crime under the relevant article of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, it is possible to talk about the further application of the norms of criminal and criminal procedural law and the imposition of a fair punishment on the perpetrator.

The classification of crimes can be considered as a legal phenomenon and as a process of cognition of objective reality. Because of this, it is necessary to consider both the criminal and legal aspects of this phenomenon (as a certain process, and as a result of this process - the preparation of criminal procedural documents), and from the point of view of what philosophical patterns and what laws of logic this activity is carried out.

Criminal law science deservedly pays great attention to the study of the classification of crimes. When analyzing any crime and the institution of the General Part of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the leading place is always occupied by the issues of qualification of crimes. In this work, the emphasis is placed on the most controversial and at the same time practically significant issues, mainly based on the analysis of qualification errors, their sources and ways to eliminate them.

When writing the work, the works of scientists V.N. Kudryavtsev, V.V. Kolosovsky, N.F. Kuznetsova were used. etc. The author also provides an overview of relevant judicial practice.

see also

- Error

- The subjective side of the crime

| Criminal law: general part | |

| General provisions | Principles of criminal law · Criminal policy · Criminal law · Criminal legislation · Action of criminal law in space · Action of criminal law in time · Retroactivity of criminal law · Extradition · International criminal law · Criminal liability |

| Crime | Classification of crimes · Qualification of crimes · Composition of a crime |

| Stages of committing a crime | Preparation for a crime · Attempted crime · Voluntary renunciation of a crime |

| Objective signs of crime | Object of the crime · Subject of the crime · Victim · Objective side of the crime · Act in criminal law · Criminal inaction · Socially dangerous consequence · Causality in criminal law · Method of committing the crime · Means and instruments of committing the crime · Place of the crime · Time of the crime · Circumstances of the crime crimes |

| Subjective signs of crime | Subject of the crime · Age of criminal responsibility · Insanity · Limited sanity · Liability of persons who committed crimes while intoxicated · Special subject · Subjective side of the crime · Guilt (criminal law) · Intent · Negligence · Innocent causing of harm · Crimes with two forms of guilt · Motive and purpose of the crime · Affect · Error in criminal law · Criminal legal regime of minors |

| Circumstances excluding the criminality of the act | Necessary defense · Causing harm when apprehending a criminal · Extreme necessity · Justified risk · Physical or mental coercion · Execution of an order or instruction |

| Complicity | Types of accomplices (performer · organizer · instigator · accomplice) · Forms of complicity (group of persons without prior conspiracy · group of persons by prior conspiracy · organized group · criminal community) · Excess of the perpetrator |

| Plurality of crimes | Aggregate of crimes · Competition of criminal law norms · Recidivism of crimes · Repeated crimes · Single crime |

| Punishment | Purposes of punishment · Types of punishment · Assignment of punishment · Conditional sentence · Exemption from criminal liability · Exemption from punishment · Pardon · Amnesty · Criminal record |

| Other measures of criminal law | Compulsory medical measures · Compulsory educational measures · Confiscation of property |

| By country | Criminal law in Canada · |

This page was last edited on June 10, 2022 at 1:30 pm.

Case studies

The practice of conducting cases involving criminal offenses indicates that their qualification is made taking into account the totality of circumstances, including signs of errors, for example:

- A type of erroneous judgment about the object of a crime. Citizen A gives a bribe to the head of a private company (citizen B), assuming that it will end up in the hands of a government official (government employee) - the crime will be classified as a bribe to an official under Article 291 of the Criminal Code.

- Citizen S. stole a firearm from citizen C., considering theft a crime. But he mistakenly failed to appreciate the responsibility for attacks on public safety. This fact can be attributed to a legal error and liability will be assigned to him under Article 226 of the Criminal Code.

- Citizen I., frightening Citizen Yu., pointed a firearm at him, being sure that it had no cartridges. After pressing the trigger guard, a shot was fired, causing a serious injury. This may mean that an error in assessing the circumstances excludes murderous intent, but is a consequence of negligence. Citizen I. was held accountable for negligence.

- Citizens K. and L. were returning from a cafe where they had been drinking alcoholic beverages. On the way we had an argument. Gr. K. inflicted multiple wounds on L. with an awl in the head and neck area. Convinced that he had committed a murder, he threw L. into the lake to conceal it. An examination by a forensic doctor showed that L.’s death was caused by water entering the lungs. Citizen K. was convicted of premeditated murder. There is an error of incorrect perception of the causes and consequences of the event.

One of the tasks of criminal proceedings is to guarantee the legality of decisions made and compliance with the rules of law.

Eliminating the problem of identifying an error at any stage of procedural actions makes it possible to take timely measures to eliminate it in the form of changing the preventive measure, terminating the criminal case, or issuing an acquittal by the court.

Error in criminal law and its impact on the limits of subjective imputation (p. 2)

' See: Yakushin on Soviet criminal law and its socio-psychological nature. In: Issues of strengthening the legal foundations of state and public life in the light of the new Constitution of the USSR. Kazan, 1980, see: Tagantsev criminal law. Lectures. General part, T. I, M., 1994, p. 235

11

error separately and show its impact on these formations. However, we always remember that it is part of the content of the latter and is always conditioned by real circumstances that predetermine this incorrect, inadequate reflection. But these real circumstances can indeed be of both an objective and subjective nature.

The definition emphasizes that an error is, first of all, a mistake regarding the circumstances that determine the nature and degree of social danger of the act. But not any circumstances, but real (actual) circumstances. Of course, the nature and degree of public danger depend on both objective and subjective signs (among the latter are guilt, motive, goal). However, when we emphasize that this is influenced by guilt, motive and purpose, then we take into account their content, forms, etc. as a whole, with all their “errors” - misconceptions, which are always possible only in relation to the real circumstances of the case. Apparently, this circumstance was not taken into account when he defined the error.

In addition, it is generally accepted that a person may be mistaken not only regarding the nature and degree of social danger of an act, but also regarding its legal characteristics, regarding its illegality. This is the same subjective circumstance that is incorrectly reflected in the psyche of the person committing a socially significant act.'

Therefore, our statement that in its most general form an error is “... a person’s misconception regarding the objective properties of a socially dangerous act that characterize it as a crime”2 seems to be the most correct. Guilt, of course, characterizes the crime as such, as a crime. But she's like

' See: A, Error in wrongfulness and its significance for determining guilt and criminal liability. In the book: Current issues of Soviet law. Kazan, 1985, sYakushin and its criminal legal significance. Kazan, 1988, p. — 35

12

was noted earlier cannot be the object of error. It exists as a reality for a person committing a socially dangerous act. For him, she is a subjective beginning, the basis of his activity. But for us, for those who look from the outside at the fact of committing a crime and state that the individual had a mental attitude to what was being committed, it appears as a given, existing (existed) objectively.

You cannot take the position that the person committing a crime, as if in a mirror, sees the mental content of guilt, motive, goal, evaluates them, incorrectly correlates them with something, and ultimately makes a mistake and commits actions on this basis.

Since, in accordance with the 1996 edition of Article 14 of the Criminal Code of Russia, a crime has two objective characteristics: social danger and criminal wrongfulness, then a person’s mistake in committing a crime concerns these characteristics. However, no; Apparently, the fundamental difference is whether an error in relation to the second objective sign of a crime should be called an error in wrongfulness or, as is the case with , should be called an error regarding the legal characteristics of the act. This does not change the essence, however, the first name for this type of error is stylistically preferable.

Taking into account the above, it can be stated that an error in criminal law should be understood as a person’s misconception regarding the nature and degree of public danger of the act being committed and its criminal wrongfulness.

§2. Classification of errors.

Classifying the mistakes of persons who committed a socially dangerous act is not the goal in itself of this or that researcher. It is carried out in the interests of a more in-depth study of this phenomenon, revealing its facets and the nature of the interaction between objective and subjective, in order to establish the real picture of what happened and the proper application of the law, in order to improve criminal legislation.

An analysis of the legal literature shows that there are many classifications of errors. In this case, the classifications are based on various characteristics.' You can, for example, classify errors according to the source of their occurrence. On this basis, we identified errors caused by: a) external, objective and b) internal, subjective factors.2 identified an error due to incorrect perception and incorrect conclusion.3 believed that on this basis one should distinguish between an error in behavior and an error due to a misconception .4 Taking into account the level of reflection of reality in the process of performing socially significant actions, we can identify an error at the level of sensory and rational reflection of reality.

We see that scientists were actively engaged in the problem of error classification even before 1917. In the pre-revolutionary criminal law of Russia, many types of errors were distinguished. Thus, the works highlight excusable and non-excusable5 errors, accidental ones,

' See: Yakushin and its significance in the application of criminal law. In the book:

Issues of implementation of rights and responsibilities in a developed socialist society. -Kazan, 1983, p.

2 See: Yakushin and its criminal legal significance. - Kazan, 1988, p. — 48

3 See: Kirichenko V.F.

The meaning of error in Soviet criminal law. - M., 1952, p.-17

4 See: Tagantsev criminal law. Lectures. Part Obshaya, T. I, M., 1994, p. -232

5 See: Tagantsev criminal law. - Part General, T. I - St. Petersburg, 1902, p.

6 Ibid., p.-581,582

14

factual and legal / In terms of its content, it singled out an error related to the act and its consequences, and an error in motives as the basis of activity.2, in addition to the factual and legal error, the error .3 N-D stood out. Sergeevsky distinguished between an error in plan and an error in execution.4

Quite a lot of attention is paid to the classification of errors in the post-October period. Thus, he identified misconceptions regarding: a) the social danger of the act; b) circumstances that are elements of a crime; c) legal factors or legal error (mistake of law).5 classified errors on the following grounds: a) by subject - legal and factual error; b) due to the reasons for its occurrence - an excusable and non-excusable error; c) in terms of its significance - the error is significant and insignificant; d) mistake guilty and innocent.6

In contrast, many scientists believe that it is necessary to distinguish not three, but two types of errors. At the same time, some believe that these are factual and legal errors7, others believe that they are errors in the object and in the circumstances related to

' Right there.

With

2 Ibid., with

3 See: Pustoroslev criminal law. A common part. - Yuryev. 1907, p. — • 344, 366

4 See: Sergeevsky criminal law (lecture manual). Part General. - St. Petersburg, 1910, p.

5 Kirichenko. cit., p. - 18

6

See:

Dagel, excluding the guilt of the subject and influencing

the

form of guilt. - Soviet justice, 1973, No. 3, p.

7 See: Koptyakov’s errors in Soviet criminal law and their classification. In the book: Problems of the law of socialist statehood and social management. - Sverdlovsk, 1978, p.; Criminal law. General part, M.: Legal. literature, 1994, p.; Criminal law of the Russian Federation. A common part. M.: Lawyer, 1996, p.; Criminal law of Russia. A common part. Textbook, M.: Publishing house Yurid. Moscow State University College, 1994, p. - 55; New criminal law of Russia (textbook). General part, M.: TEIS, 1996, p. - 52; Naumov is right. A common part. Course of lectures, M.: BEK, 1996, p.

15

objective side', according to others, this is an error regarding the objective or subjective signs of a socially dangerous act that characterize it as a crime.2

The proposed classifications of errors reflect, to one degree or another, the phenomenon under consideration, reveal some aspects of it and, for this reason, have practical significance, and hence deserve the attention of the science of criminal law. Of course, the practical significance of the above classifications is ambiguous. Some of them reveal the essential connections of a phenomenon (error) and, thus, reveal its nature, social and criminal legal significance, place in the overall relationship, etc. Other classifications help to reveal only individual sides, facets, sections of these phenomena and how they are of an auxiliary, additional nature.

The practical significance of a particular classification depends on the weight, importance, and significance of the feature that forms the basis of this classification. In addition, any classification will have greater significance, more fully and correctly reveal the content of the phenomenon, its essential moments, if its basis is chosen, which includes all objects with similar characteristics,

reasons.

If, taking these positions into account, we consider the proposed classifications of errors, then often requirements of this kind, for example, “exclusivity of the basis,” are not observed in them. Thus, the same classification feature is present in both one and the other classification. Indeed, why, for example, not consider a legal error a type of factual error? In case of a legal error, a person is mistaken regarding some fact - the legality of behavior, qualifications, type and size, punishment, etc. Researcher,

' See: Durmanov committing a crime under Soviet criminal law

right. M.: Gosyurizdat, 1956, p.

2

See:

Gilyazev guilt and the meaning of error in criminal law. Ufa, 1993

G.,

s.- 20.25

16

whoever claims that a legal error is an error regarding some factual circumstances will be absolutely right.'

On the other hand, a person’s misconception regarding factual circumstances, for example, in the object of a crime, can quite reasonably be attributed to a type of legal error, since there is a misconception regarding the type and nature of the violated social relationship, protected by certain norms of law and only by them, in relation to which there is also misconception or assessment. Believing that by violating one area of public relations, a person believes that he is violating certain norms of law. Therefore, if the culprit encroached, for example, on a person in connection with his political activities, but mistakenly took the life of another, then his criminal actions will be considered as a crime against the foundations of the constitutional order and the security of the state, and not as a crime against life and health.

Moreover, the very concept of “mistake of fact”, “factual error” does not reveal the criminal legal significance of this error, or indeed the classification itself as a whole. An error is possible, for example, in a fact that does not in any way affect the characteristics of the criminal act. In relation to the problem of subjective imputation, an error in fact does not direct the law enforcement officer to find out what significance such an error has for imputation, and hence the determination of the form of guilt, its content, etc.

It has been noted in the literature that dividing an error into excusable and non-excusable is very problematic for legal practice. In this regard, I also noted that if the error is inexcusable, then the intent is eliminated, and if the error

excusable, then all imputation is eliminated.' A similar objection was later raised.2

Let us note one inaccuracy in the reasoning and. An unexcusable mistake does not necessarily lead to a careless form of guilt. It may also be intentional. In the best case, an unexcusable mistake may indicate the presence of a careless rather than an intentional form of guilt.

We believe that such a classification of error is possible only when distinguishing between criminal and non-criminal, because each type of error in this classification emphasizes and reveals different legal poles of socially significant activity.

However, it is hardly possible to distinguish these types of errors within the framework of a criminal act. For example, a person, due to a mistake, commits not an intentional, but a careless crime. If we consider this classification through the prism of subjective imputation, it turns out that any “excusable” mistake within the framework of a socially dangerous act excludes guilt and criminal liability. In reality, “excusable” errors can change, for example, only the content and form of guilt, and hence the limits of subjective imputation, but do not exclude criminal liability as a whole.

It is of practical importance to divide an error into significant and insignificant, since it can predetermine the criminal legal assessment of the act. A person’s mistake regarding the circumstances with which the legislator associates the basis and limits of criminal liability may influence the content and form of guilt and, therefore, be considered significant. Other classifications of errors also have a certain practical significance. We have already noted that they have an additional, auxiliary character. At the same

there would be time

1 See: Tagantsev criminal law. Part General, T. I, St. Petersburg, 1902, p.

2 See: Koptyakov. worker, with

18

wrong them

ignore, underestimate, since they are a prerequisite for the main classifications, help to reveal those essential features on which they can be built, which serve as their basis and basis. That is why one should agree with the opinion of F. R. Sundurov that “a comparative analysis based on those individual, particular features that are visible to the researcher cannot be neglected as the initial stage of research.”1

The social value and practical weight of the classification of errors (as well as other phenomena) when performing socially significant actions is determined by the significance of the attribute that forms the basis of this classification.2

It is well known that a crime is an act of human behavior in which the external and internal, physical and mental, objective and subjective are represented dialectically. It is this unity of objective and subjective that is reflected in the concept of crime given by the legislator in Article 14 of the 1996 Criminal Code of Russia. It is revealed by indicating the main, essential features of the crime. A crime is a socially dangerous, illegal and guilty act committed.3

The content of the subjective side, and above all guilt, is determined by how objective and socially significant factors that determine the social danger and illegality of an act are represented in the psyche of a person and what is the attitude of the person committing this act towards them. Consequently, “a guilty act” (underlined by us. - V. Ya.) - guilt is nothing more than a reflection in the psyche

' Sundurov - psychological and legal aspects of correction and re-education of offenders. Kazan, 1976, p. — 38

2 See: , Naumov basics of classification of crimes in criminal law. - Jurisprudence, 1983, No. 2, p. — 56

3 In the criminal law literature, other signs of a crime are also highlighted. Cm.:

On the socio-psychological aspect of criminal behavior. - Alma-ata, 1971, p. - 42; Kuznetsova N. F.

Crime and delinquency.

- M.: Publishing house

Moscow. University, 1969, p. — 60, 90, 100

19

persons of public danger and the illegality of the act committed by him and the mental attitude to the circumstances that determine and reveal this danger and illegality. This interaction of external and internal and the conditionality of the latter was first noticed by the first. He wrote: “To recognize the necessity of nature and from it to deduce the necessity of thinking is materialism.”

All this allowed us to assume that the incorrect reflection in the psyche of a person of the main signs of a crime “gives rise” to two main types of error: a) an error regarding the nature and degree of social danger of the act (including consequences) and b) an error regarding the nature of the illegality of the actions committed.2

Social danger and illegality are complex, synthesizing features of a crime. It is considered an axiom that the nature and degree of public danger, for example, is determined by the object of the attack, the nature and magnitude of the consequences that occurred, the methods and means of committing crimes, etc. It follows from this that an error is possible in relation to some of the circumstances that determine the nature and degree of public danger. At one time, this allowed us to conclude that, within the framework of misconceptions regarding the nature and degree of public danger, errors can be identified: 1) in the object, 2) in the subject, 3) in the personality of the victim, 4) in the method of committing the crime, 5) in the means of the crime, 6) in qualifying circumstances, 7) in the nature of the consequences, in mitigating and aggravating circumstances.3 In addition, we also identified an error in the development of a causal relationship.4

The position we expressed was subject to criticism. It was noted that highlighting an error in the subject, the identity of the victim, the method and means

'Lenin. eobr. cit., T.18, p.

2 See: Yakushin and its criminal legal significance. — Kazan,

1988, p. — 52

3 Ibid., p. — 54

4 Ibid., with

20

the commission of a crime is hardly justified, since “they either represent types of error in the object or objective side, or have no significance at all for criminal liability.”1

What can be said about these objections? Firstly, we do not classify these types of errors as factual errors (although, of course, these are errors regarding some facts), since we emphasize their other purpose - to predetermine the nature and degree of social danger of an act. Secondly, of course, you can say that there is an error in the signs of the objective side, and then clarify which of them specifically there was an error. We believe that this does not change the essence. Thirdly, it is hardly justified to refuse such a type of error as a mistake in the subject and identity of the victim, much less to assert that they do not have criminal legal significance. It is enough to give a textbook example when the legislator associates increased responsibility with the size of the stolen property, but the person does not achieve this result due to an error, an incorrect assessment of the circumstances of the act committed.

In turn, the error of illegality can also be different. In the legal literature, this type of error is subject to gradation and division based on various characteristics.2

Since the components of the beginning of these basic, necessary signs have different criminal legal significance, then the error regarding them

plays a different criminal legal role. In some cases it changes the nature of the crime, in others - the degree of its social danger, qualifications, etc.

' Criminal law. A common part. - M.: Publishing house Yurid. lit-pa, 1994, cThe same position was expressed in the textbook - Criminal Law of the Russian Federation. A common part. - M.: Lawyer, 1996, p.

2 See, for example, Course of Soviet Criminal Law in 6 volumes. T.2. - M., 1970, p.; Naumov is right. A common part. Lecture course. - M.: Publishing house BEK, 1996, p.; Yakushin and its criminal legal significance. - Kazan, 1988, p.

21

This classification of misconceptions helps to more quickly identify and determine the direction of socially dangerous actions. We do not simply state the fact of a person’s mistake, but immediately determine what essential feature of the crime it characterizes. And if, for example, there was a mistake in the object of the crime, then it is immediately clear that the nature of the social danger of what was done is different from the actual result. The direction of action in the event of such errors is determined not by the actual result, but by the awareness (even if erroneous) of the nature of the public danger. This allows us to state that in terms of feedback, the nature and degree of social danger also depend on the content of the subjective side - guilt and its forms, the nature of the motive and goal, the emotional state of the individual. But this is the next step, the next level of defining a public danger. The level is not for the person committing the act, but for the law enforcement officer. The level when, on the basis of the imputed circumstances of the act, the mental content is determined and the final measure of the danger of the act is established by a judicial act based on taking into account the objective and subjective in the act.

| Due to the large volume, this material is placed on several pages: 2 |

Legal error

A legal error is a person’s incorrect understanding of the legal assessment of the act he has committed, or the legal liability associated with its commission[1]. A legal error can be of the following types[1]:

- An error in criminal law prohibition is an incorrect assessment of an act as non-criminal, when in fact its commission is prohibited by criminal law under threat of punishment. In most cases, to resolve the issue of liability for such an error, the principle “ignorance of the law does not exempt from liability” is applied. Criminal law establishes liability for assault due to the fact that the act actually causes harm to social relations. Even if the perpetrator does not realize the criminal wrongfulness of the act, he can and should be aware that he is causing harm to objects of criminal legal protection. Liability can be excluded only in cases where the person should not and could not have known, for example, about changes in the law that criminalized a certain act[2]. In the criminal legislation of many states (for example, Germany) such provisions are explicitly enshrined[3], while in other countries, including Russia, the practice of releasing a person from liability for such acts is based on general provisions on guilt[4].

- An imaginary crime is an erroneous assessment of an act as criminal, whereas the criminal law does not provide for such a criminal act. Such an act does not have the properties of social danger and illegality, cannot be considered guilty and therefore does not entail criminal liability.

- A person’s incorrect understanding of the legal consequences of the act (qualification, type and amount of punishment). Awareness of these elements is not included in the content of a person’s guilt and therefore does not affect its form and appearance, does not exclude it.

In general, we can say that a legal error almost never affects the measure of responsibility applied to a person.

§ 2. Qualification errors

Qualification errors are an incorrect determination of the presence or absence of a crime, as well as its compliance with the description in the norms of the General and Special Parts of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. The main sources of qualification errors are shortcomings in legislation and shortcomings in law enforcement.

Qualifying errors do not include incorrect penalties. The completion of a crime or its non-completion due to circumstances beyond the control of the person (preparation and attempt) is the limit of qualification of crimes. When qualifying crimes, the underlying post-criminal behavior is also not taken into account. It seems that there is specificity only when qualifying a continuing crime. It continues to be committed at the stage of the completed crime. In case of voluntary refusal there is no crime. Active repentance occurs after the classification of a completed or unfinished crime and affects only the punishment.

V.V. Kolosovsky considers a qualification error as “an irregularity in his actions caused by the misconception of the subject of law enforcement, consisting in an inaccurate or incomplete establishment and legal confirmation of the correspondence between the signs of the committed act and the signs of a crime or other criminal act.” These definitions are based on the incorrectness (inaccuracy or incompleteness) of the norm chosen for qualification. But how to evaluate “lack of qualifications”, i.e. when the qualifier does not find the corpus delicti where it exists? Recognizing the presence of a crime in the actions of an innocent person is, of course, the gravest mistake. Finally, in Russia, court decisions began to be made on the payment of monetary compensation, reaching millions, to persons who were wrongly brought to criminal responsibility and who served all or part of their sentence. Undoubted progress is that acquittals have become more common, including due to qualification errors.

Qualification errors can be generally classified into three groups:

1) non-recognition of the presence of corpus delicti in acts where it exists;

2) recognition of the presence of corpus delicti in acts where it is absent;

3) incorrect selection of the norm of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation to qualify the crime.

The first of these errors is widespread in prevalence. This gives rise to artificial latency of crimes (failure of law enforcement to respond to crimes that have become known to them) and deprives millions of injured citizens of the right to justice. Artificial latency is formed by law enforcement agencies, largely due to the refusal of citizens - victims of crimes to initiate criminal cases for various reasons. Among them, they are often allegedly due to the “lack of evidence of a crime,” which in fact they did not intend to discover through any operational investigative actions. There is also a large-scale cover-up of crimes by those who are professionally obliged to solve them.

As Kuznetsova N.F. points out. and we can agree with her that in some cases, investigative practice increasingly does not carry out criminal prosecution in cases of public prosecution when harm is caused to injured citizens. They demand statements from them, although the signs of a crime based on the event, and even if there is a suspect, are obvious. Cases of public prosecution are thereby transformed into cases of private prosecution, contrary to the law. This is also a technique of the main qualification error, because the legal competence of not every victim allows him to draw up a competent statement and submit it to the necessary body of inquiry or investigation.

Reacting to the prevalence of illegal refusals to initiate criminal cases, the Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation and the Minister of the Ministry of Internal Affairs on May 16, 2005 issued an order “On measures to strengthen the rule of law when issuing decisions to refuse to initiate criminal cases.” It, in particular, provides for personal liability for making illegal and unfounded decisions to refuse to initiate criminal cases due to improper behavior of officials of internal affairs bodies and the prosecutor's office. 24 hours are allotted for consideration of rejected materials from the moment they are received by the prosecutor's office. The order reminds that in accordance with paragraph 6 of Article 148 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, having recognized the refusal of the head of the investigative body, the investigator to initiate a criminal case as illegal or unfounded, the prosecutor, no later than 5 days from the date of receipt of the materials for verifying the crime report, cancels the decision to refuse initiation of a criminal case and initiates a criminal case or sends materials for additional verification with his instructions, setting a deadline for their execution.

The second, not so large-scale, but also a very serious qualifying error on an individual basis, is establishing the presence of elements of crimes in the crime, which in reality do not exist. Correction of this error by the courts (acquittals in every tenth criminal case) is an indicator of the professional competence of the judiciary. At the same time, this is a negative indicator of the work of pre-trial criminal proceedings. Such a mistake is especially condemnable when it is made in cases of grave and especially grave crimes, for example murder. Compensations for this kind of qualification errors, which began to be paid according to court decisions, are, of course, not able to compensate for the harm caused to innocent people sentenced to long terms of imprisonment.

Referring to the provisions of the Constitution, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and other international acts, the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation recognized that a court decision is subject to review if the identified significant violations committed during the previous proceedings indisputably indicate the presence of a judicial error, since such a decision does not meet the requirements of justice .

The grounds for canceling or changing a court decision when considering a criminal case in cassation and supervisory procedures (Article 401.15 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, Article 412.9 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, respectively) are significant violations of the criminal and (or) criminal procedure law that influenced the outcome of the case.

The group of qualification errors associated with an incorrect legal assessment of the offense includes “excessive” qualifications, or “qualifications with a reserve”. They are often allowed by law enforcement officers knowingly not so much because of the traditional accusatory bias, but because of the inconsistency of criminal procedural legislation. For humanitarian reasons, it prohibits the so-called “turn for the worse.” Higher courts cannot themselves, without returning the case to the courts of first instance, reclassify the crime according to a more stringent norm of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. Retraining to a more lenient standard of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation is permitted. In this regard, judges impose additional articles of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation during qualification according to the proverb “you can’t spoil porridge with butter.” The classification of the crime obviously turns out to be erroneously overstated with all the ensuing consequences. At the same time, it is not at all excluded that higher authorities may leave the erroneously toughened qualifications for indictments and sentences unchanged.