1. Cruel treatment of prisoners of war or the civilian population, deportation of the civilian population, plunder of national property in occupied territory, use in an armed conflict of means and methods prohibited by an international treaty of the Russian Federation, is punishable by imprisonment for a term of up to twenty years.

2. The use of weapons of mass destruction prohibited by an international treaty of the Russian Federation is punishable by imprisonment for a term of ten to twenty years.

What methods and means of warfare are prohibited in the Russian Federation

International humanitarian law establishes the preservation of a certain list of human rights and freedoms during armed conflict. It is prohibited to violate the rights listed in Articles 20, 21, 23, 28, 34, 40 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation. The rest may be disadvantaged during hostilities.

To avoid tragedies, Russia, like many other countries, adheres to the rules established in the Geneva Conventions for the Protection of War Victims of 1949, their Additional Protocols of 1977, etc. They describe methods and means of war that are prohibited. The first include:

- treacherous killing or wounding of persons belonging to enemy troops;

- the use of torture to obtain information about the enemy;

- murder of the envoy and his accompanying persons;

- attacks on sanitary facilities, persons who have surrendered or abandoned an airplane or other aircraft in distress (except for paratroopers);

- genocide, apartheid, as well as terror against civilians, etc.

The list of prohibited substances includes:

- bullets that easily unfold or flatten in the human body, both specially produced and subsequently adapted to such an impact;

- poisons or poisoned live ammunition;

- asphyxiating, poisonous and other similar gases;

- bacteriological (biological) and toxic weapons;

- anti-personnel mines that are not detected by publicly available mine detectors, etc.

Article 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. Use of prohibited means and methods of warfare

1. The victims are prisoners of war and the civilian population; the subject of the crime is “national property,” which should be understood as the material assets of the state, organizations and individuals in the occupied territory.

2. The objective side of the crime is expressed in a number of alternative acts:

- 1) ill-treatment of prisoners of war or civilians. The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War (1949) <1> prohibits willful murder, torture, including biological experiments, intentionally causing great suffering or serious injury, injury to health, compulsion to serve in the armed forces of an enemy power, or deprivation of rights to impartial and normal legal proceedings provided for by the Convention.

- The Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (1949) <1> adds to the above the illegal transfer or arrest, taking of hostages;

- 2) deportation of the civilian population. The Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War makes it unlawful for any reason to remove and deport civilians from occupied territory to the territory of the occupying power or another state;

- 3) plunder of national property in the occupied territory. The IV Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War on Land (1907) <1> prohibits the destruction or seizure of enemy property, unless this is caused by military necessity, or the surrender of a city or locality, even taken by storm, for plunder.

- The Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea (1949) <1> and the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (1949) criminalize large-scale activities appropriation of property of relevant persons not caused by military necessity;

- 4) the use in an armed conflict of means and methods prohibited by an international treaty of the Russian Federation. The Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949, relating to the protection of victims of international armed conflicts (Protocol I of June 8, 1977) <1> prohibits the use of weapons, projectiles, substances and methods of warfare capable of causing unnecessary injury or unnecessary suffering, and means and methods that are intended to cause or can be expected to cause widespread, lasting and serious damage to the natural environment.

The following methods of warfare are prohibited:

- treachery (feigning an intention to negotiate under a flag of truce, feigning surrender, failure due to injury or illness, having the status of a civilian or non-combatant, etc.);

- an order not to leave anyone alive;

- improper use of distinctive signs of the medical service, civil service, distinctive signs of cultural property, signs of installations and structures containing dangerous objects, and the white flag of the truce.

3. An armed conflict as a sign of the crime in question presupposes any armed actions, including military and violent ones.

4. The crime is considered completed from the moment of commission of any of the listed acts.

5. The subjective side of the crime is characterized by direct intent.

6. The subject of the crime is a person who has reached the age of 16 years.

7. The qualifying feature (Part 2 of Article 356 of the Criminal Code) is the use of weapons of mass destruction prohibited by an international treaty of the Russian Federation. The concept of such weapons is given in the commentary to Art. 355 CC.

Brief content of the article. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation with comments

The article in question, according to part one, provides punishment for persons who:

- prisoners of war and ordinary citizens were treated cruelly;

- deported civilians from their homeland;

- appropriated the property of an occupied nation;

- used in wartime methods and means prohibited by the international treaty of the Russian Federation.

Second part of Art. 356 determines the punishment for those who used weapons of mass destruction, also prohibited by an international treaty of the Russian Federation.

Comments to this norm reveal some of the terms used in the content, the degree of social danger of the offense, its composition, objective and subjective aspects.

What is the nature of the violation?

Each part of the article under consideration is devoted to a separate offense.

The danger of these acts lies in the fact that non-compliance with international law leads to a violation of people’s freedoms, an increase in victims, the destruction of homes, cultural heritage and the achievements of civilization as a whole.

An offense occurs from the moment the aggressor commits one of the actions that form the objective side of the criminal act. The occurrence of unfavorable results in this case does not play a major role. Thus, according to part two of the article under study, the consequences of the use of weapons of mass destruction are taken beyond the scope of the crime, therefore, when qualifying, the very fact of its use is taken into account.

Objective side

According to the first part of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the subjective side lies in non-compliance with the rules of the international treaty of the Russian Federation, the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. and a number of other international treaties, as well as unacceptable treatment of prisoners, the local population who found themselves in occupied territory during wartime, and theft of national property. This also includes the use of weapons and projectiles that can cause injury and pain to people and harm the environment.

In the second part of the article under consideration, the offense involves the use of weapons of mass destruction, which are prohibited by an international treaty of the Russian Federation.

The object of the above illegal actions is the trusting relationship between people, in which the obligations to conduct war on the basis of respect for the human person must be respected.

Reference . An additional object is human health and life, cultural heritage, property and nature conservation.

Subjective side

In both elements of the offense, it is necessary to identify the criminal’s malicious intent.

The subject of the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare can be a sane person over 16 years of age who takes part in hostilities. Usually these are military personnel, officials of military command and control bodies, commanders of military units and formations.

Evidence: the main problems that arise

Experts classify Article 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation as military offenses, but it is not included in them. And this is not her only problem. When qualifying actions under this article, you may encounter some difficulties.

As you already know, the offense under the first part consists of committing illegal actions prohibited by the rules of an international treaty (and other norms). The second part establishes punishment for the use of weapons of mass destruction.

Some experts claim that the second part of Art. 356 acts as a qualified type of the first part (aggravating circumstance). However, their opinion has been criticized.

In order to attribute an aggravating circumstance, the underlying element must be found. That is, in order to charge a criminal with the use of a dangerous weapon, the investigation must reveal the presence of one of the acts listed in part one of this article. And if weapons of mass destruction were used without committing them, there will be no signs of an offense.

Therefore, lawyers are inclined to believe that the article in question contains two unrelated offenses. And the simultaneous commission of acts provided for in the first and second parts must be qualified together.

This is interesting:

Responsibility for violating the rules for handling weapons under Article 349 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

What responsibility do the organizers and participants of the armed rebellion in Russia bear?

General provisions

As already announced above, the international community (in its overwhelming majority) has developed many legal documents that define the rights and freedoms of all participants in the military process, and also establish the inadmissibility of certain circumstances and actions. There are a huge number of such documents, and the following pacts and agreements are among the most important and large-scale:

- "Geneva Conventions";

- "The Hague Conventions and Declarations";

- A number of international agreements and treaties of the Russian Federation;

- Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

If we briefly consider the fundamental principles established by the provisions of these documents, we can distinguish the following types (methods) related to the topic under consideration, namely:

- Actual violation of peace and norms of human rights and freedoms;

- Causing suffering and pain to people and the environment that is not dictated by the need to conduct military operations;

- Deliberately and purposefully increasing the number of casualties among the military personnel of the defending side and/or the civilian population;

- Destruction of cultural, folk and scientific heritage.

Based on the above, the objects of the crime under consideration are formed, which include:

- human life and health;

- attitude towards property rights;

- attitude to ecology and culture;

- attitude towards infrastructure and economics.

Qualifying features

Cruelty to captives refers to any unacceptable actions outlined in the conventions of international law (for example, torture, premeditated murder, appropriation of someone else's property on a large scale, etc.).

Persons belonging to the following categories are recognized as prisoners:

- The personnel of the armed forces participating in the war, the personnel of the militia and volunteer units that are part of these armed forces.

- Military personnel of other militias and volunteer units, including personnel of organized resistance movements belonging to the parties to the conflict and operating on their territory or beyond. The specified militias and volunteer detachments must meet the following conditions: have a leader, a badge of distinction, observe the laws and customs of war in their actions, and openly carry weapons.

Deportation is considered one of the forms of cruelty. It represents the sending of the local population from the occupied territory to the territory of the occupiers or any other state. However, it is worth distinguishing such actions from forced deportation, which is carried out to protect the life and health of citizens.

The theft of national property from a occupied area consists of both theft and its appropriation by other means. The protection of cultural property is given a special place at the international level according to the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict of May 14, 1954.

The first and second parts of the article belong to the category of offenses of special gravity.

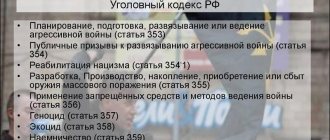

Text of the book “Crimes against the peace and security of mankind”

§ 2. Use of prohibited means and methods of warfare

2.1 General provisions on the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare

In the national criminal law of Russia, liability for the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare is established in Art.

356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. As mentioned earlier, the introduction of this norm into the criminal legislation of our country occurred under the direct influence of international criminal law and by virtue of a number of international treaties and agreements signed by the USSR and Russia. The use of prohibited methods and means of waging war (armed conflict) can be defined as the use of any method or means of waging an armed conflict prohibited by international humanitarian law, the criminality of which and responsibility for which are established in international criminal law.

Before directly considering the signs of the objective side of the crime being studied, we will try to answer two fundamental questions:

1. How many elements of crime are contained in Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation?

2. To what extent does national legislation on the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare comply with international criminal law?

Article 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation contains two parts, which define a list of acts that constitute the objective side of this crime. Part 1 refers to such acts as cruel treatment of prisoners of war or the civilian population, deportation of civilians, plunder of national property in occupied territory, and the use in armed conflict of means and methods prohibited by an international treaty of Russia. The second part deals with the criminality of using weapons of mass destruction, prohibited by an international treaty of the Russian Federation.

Let us note that in the literature there is often a point of view that the composition provided for in Part 2 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, is a qualified type of use of prohibited means and methods of warfare.[263] 263

See, for example: Criminal Law Course.

A special part. T. 5 / Ed. G. N. Borzenkova, V. S. Komissarova. M., 2002. P. 375; Nikolaeva Yu. V.

Crimes against the peace and security of mankind. M., 1999. P. 26.

[Close]

Thus, it is proposed to consider the use of weapons of mass destruction as an aggravating circumstance in relation to the acts provided for in Part 1 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

As is known, an aggravating (qualifying) circumstance increases the responsibility of the subject in relation to the commission of the main crime. However, in the sanctions Parts 1 and 2 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the upper limit of punishment is the same and amounts to 20 years of imprisonment - therefore, the maximum limits of responsibility for committing any of the acts provided for in both parts of this norm are the same and it is not possible to assert that the commission of a crime provided for in Part 2 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, is punished more severely than committing a crime under Part 1 of the same article.

But this is not even the main consideration.

The qualifying circumstance relates to the main element - that is, to impute it, it is necessary, in our case, to establish the presence of any of the acts provided for in Part 1 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. And only after this the use of weapons of mass destruction can affect the qualification of the crime. If we follow this logic, then, for example, the use of prohibited weapons of mass destruction can be imputed as a “qualifying circumstance” when committing, say, the deportation of civilians or the looting of national property in occupied territory. If the use of prohibited weapons of mass destruction occurred on its own, without the execution of any act provided for in Part 1 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, then it cannot be imputed as a “qualifying circumstance”, since the necessary characteristics of the main elements have not been established.

The absurdity of this conclusion is obvious. Committing an act under Part 2 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, is punishable initially, as well as committing any of the acts provided for in Part 1 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. Therefore, it can be assumed that in Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation contains two independent elements

crimes. Consequently, the commission by the same person of the acts provided for in parts 1 and 2 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, requires qualification of the offense in its entirety.

Let us also note one more circumstance.

Both in part 1 and in part 2 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation we are talking about the commission by the subject of any acts of behavior, i.e. deeds. The literal interpretation of the norm under study allows us to assert that any act contained in the disposition of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation is an action.

At the same time, to impute the crime under Part 1 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, it is necessary to establish the commission of at least one act (action), which allows us to talk about an alternative

the nature of the signs of the objective side of this crime.

Answering the second fundamental question (to what extent does national legislation on the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare comply with international criminal law), it should be noted that international criminal law contains a fairly extensive list of the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare:

1. “Serious violations” of the Geneva Conventions, committed during armed conflicts of an international character, affecting persons and property protected by these conventions.

2. “Other serious violations of the laws and customs applicable in international armed conflicts within the established framework of international law.”

3. “Serious violations” of the laws and customs applicable in non-international armed conflicts.

4. “Other serious violations” of the laws and customs applicable in non-international armed conflicts within the established framework of international law.

In international criminal law, war crimes generally include a fairly significant group of acts, of which over forty fall under the “use of prohibited means and methods of warfare.” There are only five such acts in the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. Does this mean that national criminal law does not correspond to international law in terms of regulating liability for the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare?

It was said above that war crimes under international criminal law include a large number of acts committed during an armed conflict and encroaching on a wide range of law-protected interests. Among the latter, it is necessary to indicate such as life and health, honor and dignity, personal and sexual freedom, and other human rights.

Consequently, the basis for identifying these acts as types of war crimes is the legal recognition of these interests as additional objects of protection during military operations. If these acts were not committed during or in connection with an armed conflict, then we can talk about ordinary crimes that do not fall under the definition of military under international criminal law.

In the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, as is known, the above-mentioned interests are independent objects of protection classified as human rights. However, the literal understanding of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation allows us to say that human rights are also an additional object of the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare. This is all the more true because for national law such factors as the time and context of committing crimes against a person do not affect the qualification of the crime, being optional signs of the objective party.

Does any criminal violation of human rights fall under Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation? Based on a comparative analysis of the limits of criminal liability for “ordinary” crimes against the person, it can be argued that for the most part - yes, except for qualified murder, which is punished more severely than the acts provided for in Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

Thus, it is permissible to assert that when qualifying the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare according to the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the commission of any “common criminal” crime against a person, with the exception of murder under aggravating circumstances, does not require additional qualification (Part 2 of Article 105 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation).

Based on this, we can conclude that the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation generally complies with the provisions of international criminal law in the field of regulating liability for the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare.

2.2. The objective side of the use of prohibited means and methods of warfare

Abuse of prisoners of war or civilians.

The legislator directly defines the circle of victims of “cruel treatment”, speaking about prisoners of war and the civilian population. To correctly understand the legal status of these categories of persons, it is necessary to refer to acts of international law.

prisoners of war,

within the meaning of Art. 4 of the Third Geneva Convention are persons who fall into the power of the enemy during an armed international conflict and belong to one of the following categories:

1. The personnel of the armed forces of the party to the conflict, as well as the personnel of the militia and volunteer units that are part of these armed forces.

2. Personnel of other militias and volunteer units, including personnel of organized resistance movements belonging to a party to the conflict and operating on or outside their own territory, even if that territory is occupied, if these militias and volunteer units, including organized movements resistance, meet the following conditions:

a) are headed by a person responsible for his subordinates;

b) have a distinctive distinctive sign that is clearly visible from a distance;

c) openly carry weapons;

d) comply in their actions with the laws and customs of war.

3. Members of regular armed forces considering themselves subordinate to a government or authority not recognized by the detaining Power.

4. Persons following the armed forces, but not directly included in them, such as, for example, civilian members of the crews of military aircraft, war correspondents, suppliers, personnel of work teams or services entrusted with the welfare of the armed forces, provided that they have received permission to do so from the armed forces they are accompanying, for which purpose the latter must issue them an identity card of the attached sample.

5. Members of the crews of merchant marine vessels, including captains, pilots and cabin boys, and civil aviation crews of parties to the conflict who do not receive preferential treatment under any other provisions of international law.

6. The population of an unoccupied territory, who, when the enemy approaches, spontaneously, on their own initiative, take up arms to fight the invading troops, without having time to form into regular troops, if they openly carry weapons and comply with the laws and customs of war.

In Art. 43 I of the Additional Protocol defines that the armed forces of a party to the conflict consist of all organized armed forces, groups and units under the command of a person responsible to that party for the conduct of his subordinates, even if that party is represented by a government or authority not recognized by the opposing party. Such armed forces are subject to an internal disciplinary system which, among other things, ensures compliance with international law applicable in armed conflicts.

Persons who are members of the armed forces of a party to the conflict (except for medical and religious personnel referred to in Article 33 of the Third Convention) are combatants, i.e. they have the right to take direct part in hostilities.

In accordance with Art. 44 I of the Additional Protocol, any combatant who falls into the power of the opposing party is a prisoner of war.

Although all combatants are obliged to comply with the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, violations of these rules do not deprive the combatant of his right to be considered as such or, if he falls into the power of an adverse party, of his right to be considered a prisoner of war, except as provided in paragraphs 3 and 4 Art. 44 I of the Additional Protocol, namely:

“1) In order to help enhance the protection of the civilian population from the consequences of hostilities, combatants are required to distinguish themselves from the civilian population while they are participating in an attack or a military operation in preparation for an attack. However, since during armed conflicts there are situations where, due to the nature of hostilities, an armed combatant cannot distinguish himself from the civilian population, he retains his combatant status provided that in such situations he openly carries his weapon:

a) during every military conflict;

b) while he is in full view of the enemy during deployment in battle formations preceding the commencement of an attack in which he is to take part.

Actions that meet the requirements of this paragraph are not considered treacherous.

(2) A combatant who falls into the power of the adverse party while he fails to comply with the requirements laid down in the second sentence of paragraph 3 shall be deprived of the right to be considered a prisoner of war, but shall nevertheless be accorded protection equivalent in all respects to that accorded to prisoners of war in in accordance with the Third Convention and this Protocol. Such protection shall include protection equivalent to that accorded to prisoners of war under the Third Convention in the event that such person is tried and punished for any offenses which he has committed.”

Further, Additional Protocol I states that any combatant who falls into the power of the opposing party when he is not participating in an attack or in a military operation in preparation for an attack does not lose his right to be considered a conbatant and a prisoner of war by virtue of his previous actions. .

The above provisions of the Additional Protocol are “without prejudice” to the right of any person to be considered a prisoner of war in accordance with Art. 4 of the Third Convention.

The Third Geneva Convention also establishes a list of persons whose legal status is equivalent to

to the status of a prisoner of war (clause b of article 4). These include:

"1. Persons who belong or have belonged to the armed forces of an occupied country, if the Occupying Power considers it necessary for reasons of their belonging to intern them, even if it initially released them, while hostilities were taking place outside the territory it occupied, especially when these persons unsuccessfully tried to join the armed forces to which they belong and which are taking part in hostilities, or when they have disobeyed a challenge made for their internment.

2. Persons belonging to one of the categories enumerated in this article who have been received into their territories by neutral or non-belligerent Powers and whom those Powers must intern in accordance with international law, unless they prefer to accord them more favorable treatment; however, these persons are not subject to the provisions of Articles 8, 10, 15, fifth paragraph of Article 30, Articles 58-67, 92, 126, and in cases where diplomatic relations exist between the parties to the conflict and the neutral or non-belligerent Power concerned , as well as the provisions of the articles relating to the Protecting Powers. Where such diplomatic relations exist, the Parties to the conflict to whom such persons are included shall be permitted to exercise in relation to them the functions of the Protecting Power provided for in this Convention, without prejudice to those functions which such parties ordinarily exercise under diplomatic and consular practice and treaties.”

Thus, we can rather talk about two categories of victims, defined as “prisoners of war”

in an armed conflict of an international nature, namely: a prisoner of war in the strict sense of the word (a combatant who has fallen under the power of the opposing side) and a person equal in status to a prisoner of war (Article 4 of the Third Geneva Convention, Articles 43 and 44 of the First Additional Protocol) .

The Convention applies to the persons specified in Art. 4, from the moment they fall into the power of the enemy until their final release and repatriation (Article 6 of the Third Geneva Convention).

If, in relation to persons who took one or another part in hostilities and fell into the hands of the enemy, doubt arises as to their belonging to one of the categories listed in Art. 4, such persons will enjoy the protection of the Convention until their position is determined by a “competent court”.

Consequently, if there is doubt about a person’s status as a prisoner of war, a legal (judicial) procedure has been established to determine the applicability of the provisions of the Third Geneva Convention to such a person.

The definition of “prisoner of war” is not applicable to non-international armed conflicts - Additional Protocol II uses the term “persons whose freedom is restricted for reasons related to armed conflicts.”

Due to such provisions of international criminal law, militants captured during the military campaign in Chechnya, for example, are not considered prisoners of war.

Prisoner of war status also does not apply to spies and mercenaries

(Articles 46, 47 I Additional Protocol).

A spy, notwithstanding any other provision of the Geneva Conventions, is any member of the armed forces of a party to the conflict who falls into the power of the opposing party while engaged in espionage.

At the same time, persons who:

a) are members of the armed forces of a party to the conflict and collect or attempt to collect information on behalf of that party in territory controlled by the opposing party (provided that such persons wear the uniform of their armed forces);

b) are members of the armed forces of a party to the conflict, reside in territory occupied by an opposing party, and on behalf of a party on which they depend, collect or attempt to collect information of military significance - unless such persons act fraudulently or intentionally do not resort to secret methods;

c) are members of the armed forces of a party to the conflict, do not reside in territory occupied by the opposing party, and are engaged in espionage in that territory (except in cases where such persons are captured before they have rejoined the armed forces to which belong).

In accordance with Art. 47 I Additional Protocol, mercenary

is any person who has the following characteristics:

a) specially recruited locally or abroad for the purpose of fighting in an armed conflict;

b) actually takes direct part in hostilities;

(c) takes part in hostilities motivated primarily by the desire for personal gain and is in fact promised by or on behalf of a party to the conflict material remuneration substantially in excess of that promised or paid to combatants of the same rank and function, members of the armed forces of this party;

d) is neither a citizen of a party to the conflict nor a person permanently residing in the territory controlled by a party to the conflict;

e) is not a member of the armed forces of a party to the conflict;

f) is not sent by a State which is not a party to the conflict to perform official duties as a member of its armed forces.

In recent history there are precedents for the non-extension of the status of prisoners of war to persons taking part in terrorist activities

. And this is quite fair, since persons waging armed terrorist struggle of an international nature (be it the Taliban or Chechen militants) themselves, by definition, do not comply with any laws and customs of warfare.

US Secretary of Defense D. Rumsfeld said that militants of the Al-Qaeda group and the Taliban captured in Afghanistan were delivered to Cuba to the US Naval Base Guantanamo Bay. According to him, the militants brought to Cuba “will be considered not prisoners of war, but persons who waged an illegal armed struggle. Thus, technically they are not covered by the Geneva Convention.” “However, we intend to treat them mainly in accordance with this convention,” the Pentagon chief emphasized. At the same time, he noted that the task of the anti-terrorist operation “is not to capture one or two more terrorist leaders or to stop the activities of one group, but to fight terrorism, wherever it exists.”[264] 264

ITAR-TASS report dated January 12, 2002

[Close]

Apparently, this judgment is fair and applicable to international terrorists entrenched in Chechnya.

Definition of civilian population

contained in the IV Geneva Convention (Articles 3, 4). These include:

a) persons who do not directly take part in hostilities;

b) persons from the armed forces who have laid down their arms;

c) persons who ceased to take part in hostilities due to illness, injury, detention (of course, with the exception of military captivity) or “for any other reason.”

The category of civilian population also includes persons who, at any time and in any manner, in the event of a conflict or occupation, are in the power of a party to the conflict or of an occupying power of which they are not nationals.

The provisions of the cited Convention stipulate that the said categories of "civilian population" shall in all circumstances be treated humanely without any discrimination on grounds of race, colour, religion or creed, sex, birth or property or any other similar criteria.

At the same time, in Art. 4 it is determined that citizens of any state not bound by the Convention are not under its protection. Citizens of any neutral state located on the territory of one of the belligerent states, and citizens of any co-belligerent state will not be considered as protected persons so long as the state of which they are citizens has normal diplomatic representation in the state in power which they are located.

In Art. 50 I of the Additional Protocol makes a legal distinction between the concepts of “civilian” and “civilian population”.

Thus, a “civilian” is any person who does not belong to any of the categories of persons specified in Art. 4 of the III Geneva Convention and in Art. 43 I of the Additional Protocol.

In turn, the “civilian population” consists of all persons who are civilians. Crucially, the presence of individuals among the civilian population who do not fall within the definition of civilians “does not deprive that population of its civilian character.”

In case of doubt as to whether a person is a civilian, he is considered to be such. This provision of the Protocol is especially relevant for our country, which has been conducting an anti-terrorist operation in Chechnya for several years.

It is well known that the actions of the Russian armed forces are subject to massive criticism both within the country and abroad for “excessive rigidity” and “indiscriminateness” in terms of striking targets in Chechnya. We will not try to give a political assessment of the situation - this is not our task. Let us note that when deciding whether the population of Chechnya falls under the definition of “civilian population” (and therefore whether a war crime is being committed against them or not), it is necessary to constantly remember the said “rule of interpretation of the doubt”: if there are no sufficient arguments against, then the person must be considered to belong to the civilian population.

Finally, it must be remembered that these rules of international law on the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts do not apply to cases of disruption of internal order and the emergence of a situation of internal tension, such as riots, isolated and sporadic acts of violence and other acts of a similar nature, since such are armed conflicts (Article 1 II of the Additional Protocol).

In Art. 48 I of the Additional Protocol specifically states that, in order to ensure respect and protection of the civilian population and civilian objects, parties to a conflict must always distinguish between the civilian population and combatants, and between civilian and military objects, and accordingly direct their actions only against military objectives .

In Art. 13 of the Second Additional Protocol establishes that the civilian population and individual civilians enjoy general protection against the dangers arising from military operations in a non-international armed conflict.

In order to implement this protection, the following rules are observed in all circumstances:

a) the civilian population as such, as well as individual civilians, must not be the object of attack;

b) acts of violence or threats of violence whose primary purpose is to terrorize the civilian population are prohibited.

Civilians enjoy protection during non-international armed conflicts, unless and for such a period as long as they themselves take a direct part in hostilities.

So, the category “civilian population”

in an armed conflict of an international nature, all persons located on the territory of the conflicting states who are not combatants (not regarded as combatants), spies and mercenaries; in non-international conflicts - persons who do not take part in hostilities.

In Part 1 of Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, one of the acts that form the objective side is “cruel treatment” of prisoners of war or the civilian population.

Unfortunately, the law does not provide a textual definition of the term “abuse.” In the domestic legal doctrine, the category “special cruelty in the commission of a crime” has been developed. Thus, in the legal literature, judgments have been made that special cruelty is associated with the manifestation by the perpetrator of “extreme severity,” “heartlessness,” “inhumanity,” “ruthlessness,” “ruthlessness.”[265] 265

Borodin S.V.

Qualification of crimes against life.

M., 1977. S. 131–132; Zykov V.

Special cruelty as a circumstance qualifying murder // Soviet justice. 1969. No. 6. P. 15, etc.

[Close]

In Russian, the word “cruelty” means “extreme severity, ruthlessness, mercilessness, heartlessness.”[266]266

See:

Ozhegov S.I.

Decree. op. pp. 188–189.

[Close]

What is meant by cruel treatment of prisoners of war and civilians?

A number of authors say that cruelty is “the deliberate use of physical and/or mental violence,” and the scope of such violence includes “murder, bodily harm or beating, bullying, humiliation of human dignity, and assault on sexual integrity.” [267] 267

Antonyan Yu. M.

Cruelty in our lives. M., 1995. P. 101.

[Close]

Many works are devoted to the analysis of violence in criminal law, but in them, as a rule, there is no distinction between the concepts that interest us.

In Russian, “to use violence” (“to rape, to force”) means “to force, to coerce, to force something by force, to force.” Accordingly, “violence” is “coercion, bondage, need, force.”[268] 268

Dal V.I.

Explanatory dictionary of the living Great Russian language. T. II. M., 1998. P. 468.

[Close] Let us note right away that in the generally accepted sense, “violence” and “coercion” act as synonyms with almost the same semantic load. This tradition continues in modern philology.[269] 269

Indeed, in S.I. Ozhegov we read: “Violence is ... forced influence on someone (something).”

See: Ozhegov S.I.

Decree. op. P. 344.

[Close]

One of the most detailed definitions of violence was proposed by A.V. Ivashchenko and A.I. Martsev, who believe that “violence should be considered active conscious activity (behavior) directly directed against free expression of will. With this understanding of violence, its phenomenal feature should be considered the infliction of harm on the one whose freedom is limited, against whose free will the act is inflicted.

Unlike many other forms of manifestation of human activity, only violence is behavior in which a person’s actions are obviously aimed at suppressing freedom.”[270] 270

Ivashchenko A.V., Martsev A.I.

Methodology of legal research of violence // Social and legal problems fight against violence. Omsk, 1996. P. 4.

[Close] another person or other people.

In the domestic doctrine of criminal law, violence is traditionally divided into physical and mental.

Physical violence

characterized by the following features:

1) It is an effect on the body of another person

(both on the body as a whole and on its biological components - organs and tissues).

Almost all authors say that a sign of physical violence is its unauthorizedness - that is, the infliction of violence against the will of the victim. Thus, for example, exceptions to the prohibition on the removal of tissue or organs for transplantation can only be made in the case of donating blood for transfusion or skin for transplantation, provided that this is done voluntarily and without any coercion or inducement, and only for therapeutic purposes , in conditions that comply with generally recognized medical standards, and under control aimed at the benefit of both the donor and the recipient (Part 3 of Article 11 I of the Additional Protocol).

2) By its nature, physical impact can be “energetic”

[271]

271 Boytsov A.I.

The concept of violent crime // Criminological and criminal legal problems in the fight against violent crime. L., 1988. P. 138.

[Close] – factors of energy violence in the literature include: mechanical impact; physical impact in the narrow sense; chemical exposure achieved by using chemically active substances in any state of aggregation (toxic, potent substances, etc.); biological impact - i.e. the introduction into the body of another person of pathogenic microorganisms (bacteria, viruses) or their metabolic products (biological toxins).

In turn, mental violence

is an aggressive impact on

the psyche of another person.

Unlike physical, such impact is informational in nature and consists of an information process occurring between the person causing the harm and the injured person. This process includes the “information processing cycle” (transmission, perception, conversion and storage of signals).

The subject of mental violence is not the human body (human organs and tissues, as well as their functions), but the human psyche. The concept of the human psyche is extremely diverse and covers the entire spectrum of mental phenomena (conscious and unconscious, will, emotions, mental states, etc.).

Punishments for criminals

In both parts of Article 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, criminal liability is a prison term, the upper limit of which is 20 years . There are no minimum deadlines.

In what cases is criminal liability not imposed?

Since the content of the article in question affects military personnel to a greater extent, it is permissible to use Article 42 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation “Execution of orders and instructions,” which excludes the criminality of the committed acts.

The Disciplinary Regulations state that subordinates are obliged to unquestioningly carry out the orders of their commanders. Violation of the order entails disciplinary or criminal liability. But what should an employee do if the demands given contradict international law?

The legislation establishes that the infliction of such damage by a person acting not out of his own personal motives, but within the framework of an order, does not bring the performer to criminal liability (part one of the article in question). The person who knowingly gave illegal instructions will be held responsible.

Note : Responsibility under Art. 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation can be excluded in the case where the executor of the order did not have the right to refuse the demands of the superior and was obviously not aware of their illegality.

Judicial practice under the article

An extensive legal framework has developed at the national and international levels to combat crimes during armed conflicts. However, its presence does not exclude the commission of war crimes.

In Russia, criminal cases are rarely brought against such offenses. There are no examples from practice under Article 356 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, however, actions that fall under the criteria of its qualification, but were not assessed accordingly, did take place.

For example , according to the first part of the article being studied, they should have qualified the order of the direct commander of the group, Captain Ulman, who on January 11, 2002 issued an order to shoot five captured citizens near the village of Dai. Three local residents from the outskirts of Staraya Sunzha were killed in a similar way on November 15, 2005.

Atrocities do not go completely unpunished. They are qualified under other articles of the Criminal Code related to military offenses (for example, murder, violence, causing damage in the form of severe bodily injury, etc.).