The concept and meaning of proof and evidence

Evidence and proof in criminal proceedings represent factual data on the basis of which the following must be established:

- Guilt of the person.

- The presence or absence of danger in the act.

- Other circumstances that are integral to the case.

The importance of evidence is determined by the fact that with the help of it, all factual data can acquire high reliability, which will be sufficient for informed conclusions regarding the guilt of a person.

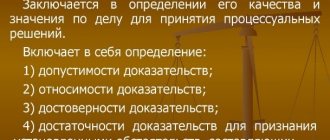

Article 88 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation. Rules for evaluating evidence (current version)

1. Evaluation of evidence is a mental logical activity to determine the relevance, admissibility and sufficiency of evidence for making a particular procedural decision. It represents an element of the process of proof, i.e. accompanies the entire process of collecting and verifying evidence (ongoing assessment of evidence). However, the assessment takes on the character of an independent stage of proof, when, based on the totality of the collected evidence, it serves to determine the presence or absence of grounds for making procedural decisions (final assessment of evidence). The assessment of evidence has a procedural form, which either has a generalized form of presentation in procedural decisions of the conclusions drawn on its basis, or in cases established by law - the very process of substantiating these conclusions (the motivation for the procedural decision at the factual level). The law imposes completeness and consistency requirements on the motivation of procedural decisions. Completeness lies in the fact that from the substantiation of conclusions about the presence or absence of the circumstances of the case, none of the evidence collected in the case should be excluded. If certain evidence is found to be of poor quality, the investigator, inquiry officer, prosecutor and the court are obliged to indicate in their final decision (indictment or act, decision to terminate the case or criminal prosecution, sentence, etc.) why they accept some of the evidence and rejected by others. Thus, if the court’s verdict states that the court trusts the testimony of the victim and the prosecution witness and considers them truthful, it must indicate on what specific grounds the court accepted this testimony and rejected the defendant’s testimony that contradicted it. In this case, the only insufficient motivation is the reference to the fact that by denying guilt, the defendant is trying to evade responsibility, since this cannot replace a meaningful assessment of the evidence. Circumstances recognized as established on the basis of evidence and specified in the same procedural act must also not contradict or be mutually exclusive. Such a defect will occur, for example, if in the operative part of the court sentence the person accused of robbery is charged with using violence dangerous to life and health, although in the descriptive part of the sentence the court agrees with the conclusion of the forensic expert that only slight harm was caused to the victim health, and does not provide evidence that the victim was otherwise placed in a life-threatening condition by the accused.

2. The directions for assessing evidence in this article are the relevance, admissibility, reliability and sufficiency of evidence. On the relevance and admissibility of evidence, see the commentary. to Art. Art. 74, 75 of this Code.

The reliability of evidence is the idea of the truth of the information contained in it. The criterion of truth can only be experience and practice. Therefore, only such a conclusion can be considered reliable knowledge about the circumstances of the case in relation to which, to use the apt expression of the Anglo-Saxon procedural doctrine, there are no reasonable doubts, i.e., in other words, there are no exceptions from public practical experience, and primarily from experience, concentrated in the totality of evidence collected in the case. Reliability based on evidence is proof of the circumstances of the case.

The sufficiency of evidence is determined in part 1 of the commentary. article as the sufficiency of the entire body of evidence collected in the case to resolve the criminal case. However, sufficiency of evidence does not always equate to proof (reliability of establishing) the event of a crime, the guilt of a person in committing it and other circumstances to be established in a criminal case. Thus, evidence that leaves doubt about the existence of a crime or the guilt of a person in committing it may be sufficient to terminate a criminal case.

Comment source:

Ed. A.V. Smirnova “COMMENTARY ON THE CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION” (ARTICLE BY ARTICLE), 5th edition

SMIRNOV A.V., KALINOVSKY K.B., 2009

Testimony of the suspect, accused

Evidence in a criminal trial includes the testimony of the accused person as well as the suspect. The interrogation of a suspect is carried out no later than 24 hours after the initiation of a criminal case (with the exception of cases where the whereabouts of the suspect have not been established).

If the case was initiated on the basis of a crime and during the inquiry process information was obtained that is sufficient to suspect a person of the committed act, the investigator draws up a notice of suspicion of a crime. A copy of the document is given to the suspect. After this, the investigator will be required to conduct a substantive interrogation within 3 days.

The testimony of the accused, in turn, is divided into the following types:

- Admission of guilt - the evidentiary value in this case is to obtain information about the circumstances that will help subsequently solve the crime.

- Denial of guilt - to confirm this testimony, employees must check the so-called alibi.

- Giving evidence against other persons - such information is called slander.

Testimony of the victim, witness

Evidence in a criminal trial in the form of testimony from the victim implies information about any of his relationships with the accused. The subject of the testimony is the circumstances that will subsequently be subject to proof. Data that is not supported by specific sources of its receipt is not considered evidence.

Differences between the testimony of a witness and a victim include the following features:

- A person who was affected by the consequences of the crime is interrogated as a victim, and any person can act as a witness.

- The witness has no interest in the case, while the victim pursues his own interests.

- Giving testimony of a witness is his direct responsibility, and for the victim it is also a right.

- The victim is present throughout the trial.

- The victim can participate in court arguments regarding private prosecution cases.

Evidence is classified according to various criteria or grounds. The classification of evidence is of great importance, both theoretical and practical. The division of evidence indicates the amount of means and methods of proof available to the court, reveals the characteristics of certain types of evidence, which are important to take into account in the process of collecting, researching and evaluating it, and helps to avoid errors in judicial proceedings.

The first group of classification of evidence is their division according to the method of formation into primary and derivative.

Primary – refers to evidence obtained from a primary source. Derivatives, in turn, are proofs that reproduce the content of another proof. They are received “second-hand”.

The initial evidence will be the testimony of a witness who learned about the fact from another person and will be derivative. The original document (for example, a driver's license) is the initial evidence; and a copy from it is a derivative. Traces left on the ground or objects are original, casts from traces are derivative.[1]

Initial proofs have an undeniable advantage over derivatives. The initial proof always comes from the original source. Derivative evidence arises on the basis of the initial one; it can also be reliable, but the court must approach its assessment with caution. When analyzing initial and derivative evidence, the main attention in the legal literature is paid to derivative evidence, i.e. They are the ones that conceal the possibility of making mistakes in the process of their formation.

According to the principle of immediacy, the court should primarily examine the facts of the case from primary sources, and derivative evidence should be used primarily as a means of discovering primary sources.

The practical significance of this classification lies in the importance of the process of forming this and other evidence, it allows you to correctly conduct the process of examining evidence during the trial, correctly pose the question to the party, witness, expert and find out the information necessary in the case.

The court cannot refuse to include evidence in the case because it is not the primary source. The reliability of both initial and derivative evidence is assessed by the court as a result of comparing both with all the materials of the case.

Based on the nature of the conclusion, forensic evidence is divided into direct and indirect.

Direct evidence is evidence that, even taken separately, makes it possible to draw only one definite conclusion about the fact being sought.

Indirect evidence, taken separately, provides the basis not for a definite, but for several conjectural conclusions, several versions regarding the sought-after fact. Therefore, indirect evidence alone is not enough to draw a conclusion about the sought-after fact. Indirect evidence, taken not separately, but in connection with the rest of the evidence in the case, then, when comparing them, it is possible to discard unfounded versions and come to one definite conclusion.

Indirect evidence can be used not only as an independent means, but also in conjunction with direct evidence, reinforcing it, or, conversely, weakening it. [2]

Direct evidence does not always play a greater role than indirect evidence. In judicial practice, indirect evidence is used widely in civil cases in cases where there is no direct evidence in the case or there is insufficient evidence. However, the use of indirect evidence is more difficult than direct evidence. The task of the court in relation to direct evidence is to establish and test the reliability of such evidence. Having checked and established their reliability, the use of direct evidence does not present any obstacles, since the sought fact is directly confirmed or refuted.

The practical significance of dividing evidence into direct and indirect is that the differences between this evidence are taken into account by the judge when collecting evidence. Circumstantial evidence must be in such a volume that it is possible to exclude all assumptions arising from it, except one.

The presence of direct evidence does not exclude the possibility of refuting its content. Direct and indirect evidence influence the content of judicial evidence: the use of indirect evidence lengthens the path of proof and introduces additional steps for the court on the path to resolving the main issues of the case.

The differences between direct and indirect evidence require corresponding consideration of their characteristics when assessing the evidence. Direct, like indirect, evidence does not have a predetermined force for the court and must be assessed in conjunction with other evidence.

There is another type of classification of evidence: dividing it by source.

The source is understood as a certain object or subject on which or in whose consciousness various facts that are important for the matter are reflected.

Based on the source of evidence, evidence is divided into personal and material.

Personal evidence includes explanations of the parties and third parties, testimony of witnesses, and expert opinions. Physical evidence may include objects of the material world.[3]

The classification of evidence allows us to conclude that none of the classifying features gives the advantage of one piece of evidence over another when examining and evaluating it. The classification reveals the features of various means of proof and the information about the facts that is collected using these means and contributes to the correct assessment of evidence.

[1] Zaitsev I.M. Vikut M.A. Civil process in Russia. – M., 1999. – p.167

[2] Shakaryan M.S. Civil procedural law. – M.: 2004. – p. 180

[3] Musina V.A. Chechina M.A. Chechota D.M. Civil process M., 1998. – p. 181

Evidence

In general terms, they represent the consequences of a criminal act. Physical evidence can be in the form of things in the material world that were subject to change as a result of a criminal act. Their evidentiary value is considered to be their location (for example, a stolen item found), the fact of their creation (a fake document), or their actual properties (configuration, as well as the size of the criminal’s footprints).

Classification and types of evidence obtained as a result of investigative activities:

- Items that served as a crime weapon (weapons, sharp objects).

- Items that have retained traces of a criminal act (items damaged by firearms, clothing with blood stains).

- Money and valuables acquired illegally.

- Items that have been the target of attacks (stolen items or valuables).

Why is inadmissible evidence acceptable?

If laws could speak out loud, the first thing they would complain about was the lawyers. D. Halifax

Let's consider other positions of the adopted Resolution of the Plenum of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation dated December 19, 2017 No. 51 “On the practice of applying legislation when considering criminal cases in the court of first instance (general procedure of legal proceedings)” regarding the inadmissibility of evidence (the first part of the material can be found by clicking on the link ).

Paragraph 5 of the resolution states: “Motions received before the start of the consideration of the case or stated in the preparatory part of the court session for the calling of new witnesses, experts, specialists, for the demand of material evidence and documents or for the exclusion of evidence obtained in violation of the requirements of the criminal procedure law , as well as petitions related to determining the circle of participants in the trial and the progress of the case (on recognition as a victim, a civil plaintiff, on postponing or suspending the trial, termination of the case, etc.) are resolved immediately after their application and discussion.”

This position of the Plenum of the RF Armed Forces meets the requirements of Part 1 of Art. 121 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation that the petition is subject to consideration and resolution immediately after its application.

This prevents the widely spread judicial-prosecutor's tricks that the petition was filed prematurely, the evidence has not yet been examined, etc., which is accompanied by the possibility of postponing the consideration of the petition until going to the deliberation room to announce the verdict. Thus, inadmissible evidence is unreasonably allowed to be examined during a judicial investigation, when it should be excluded at earlier stages.

However, further in the same paragraph it is stated: “In the absence of sufficient data necessary to resolve the petition in this part of the trial, the judge has the right to invite the parties to submit additional materials in support of the stated petition and assist them in obtaining such materials, as well as take other measures, allowing a lawful and justified decision to be made, provided for in Part 2 of Article 271 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation.”

I believe that the clarification made could relate to the resolution of other requests (for example, to call a witness whose address is unknown), but not requests to exclude evidence, for which the request for additional data is not required. Controversial evidence is always found in the materials of the criminal case, and the task of the court is to immediately check it for admissibility.

The above position of the Plenum of the RF Armed Forces is bad in that if the judge wants to evade the resolution of the submitted petition to exclude evidence, he will be able to postpone its consideration under the far-fetched pretext of the need to provide additional data. And the construction “in the absence of sufficient data” leaves room for judicial subjectivity.

In such a situation, the task of the defense is to demand resolution of the petition directly, as prescribed in Part 1 of Art. 121 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, and at the same time prove that there is no need to request additional materials.

The arsenal of negative possibilities is contained in paragraph 6 of the resolution: “On those issues that are specified in part 2 of Article 256 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, the court issues a resolution or determination in the deliberation room in the form of a separate procedural document, which is signed by the entire composition of the court. Other issues may be resolved by the court, at its discretion, both in the deliberation room and in the courtroom with the entry of the adopted resolution or ruling into the minutes of the court session. In all cases, the court decision must be reasoned and announced at the court hearing.”

In accordance with Part 2 of Art. 256 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, petitions to exclude evidence are not included in those issues that are considered by the court in the deliberation room and which are presented in the form of a separate procedural document signed by the judge. In this regard, the Plenum of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation invites judges to decide for themselves whether to consider such petitions in the deliberation room or in the courtroom with the entry of the adopted decision into the minutes of the court session. And this, in my opinion, is a serious problem.

In the courtroom, it is possible to resolve a request, for example, to question an expert, which does not require special intellectual effort. But petitions to exclude evidence, as a rule, are voluminous, may contain a list of procedural violations on dozens of sheets, require careful verification, taking into account not only the norms of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation and other laws, but also judicial practice, comparison of the positions of the defense and prosecution, etc. Resolving motions to exclude evidence based on time costs is sometimes no different from passing a verdict and is a very labor-intensive task.

Is it possible to resolve such motions by conferring on the spot and without going to the deliberation room?

It seems that even the most brilliant judges, after hearing a voluminous petition, are not able to immediately figure out whether it is justified or not and impromptu announce a reasoned ruling.

It is no coincidence that the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation in its Ruling of July 12, 2005 No. 323-O “On the refusal to accept for consideration the complaint of citizen Vladislav Igorevich Sheichenko about the violation of his constitutional rights by Articles 17, 88, 234 and 235 of the Criminal Procedure Code of the Russian Federation” emphasized: “There are no grounds for accepting V.I.’s complaint for consideration. Sheichenko and in the part concerning challenging the constitutionality of Articles 234 and 235 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation as not providing for the need to make a separate decision on declaring evidence inadmissible, since the very presentation of the judge’s conclusions regarding the admissibility or inadmissibility of evidence is not in the form of a separate procedural decision, but as a component parts of the decision made as a result of the preliminary hearing (in particular, on the appointment of a court hearing) do not violate the constitutional rights of the applicant. The need for a judge to make a written decision on a party’s request to declare evidence inadmissible, as well as the procedural procedure for making such a decision, contrary to the opinion of the applicant, is established both by the contested and other norms of the criminal procedure law, including Article 236 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation .”

It should be recalled that, in accordance with the requirements of Part 4 of Art. 236 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, “if the judge grants a petition to exclude evidence and at the same time schedules a court hearing, then the decision indicates what evidence is excluded and what materials of the criminal case that justify the exclusion of this evidence cannot be examined and announced at the court hearing and used in the process proof."

Although this procedural rule applies to the preliminary hearing, there is no reason to ignore it at later stages of the trial.

The Supreme Court of the Russian Federation actually allowed judges to independently decide when to retire to the deliberation room and when not. Using this clarification, judges will be able to make decisions on complex petitions to exclude evidence without going to the deliberation room, without giving answers to all the arguments of the petition, limiting themselves to general phrases, only formally giving their resolution a motivated appearance. Every practicing lawyer will be able to give a lot of examples when judges did this before the adoption of the decision of the Plenum under consideration.

It would seem that the current procedural rules do not relieve the judge from the obligation to make a lawful, reasoned and substantiated judgment on the stated petition to exclude evidence, for example, in a verdict. However, I have not yet encountered a single appeal ruling that overturned the verdict of the trial court due to improper consideration of these petitions.

The proposed free approach to the procedure for resolving requests to exclude evidence obtained in violation of the law will, in practice, aggravate the emerging crisis of this procedural institution.

It is necessary to evaluate positively paragraph 13 of the resolution, according to which “the courts should keep in mind that the rules established in part 4 of Article 235 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation for a preliminary hearing, according to which, when considering the defense’s request to declare evidence inadmissible on the grounds that it was obtained in violation of the requirements of the criminal procedure law, the burden of refuting the defense’s arguments rests with the public prosecutor, and in other cases the burden of proof lies with the party filing the petition , and extends to the trial.”

If we simplify the complex construction of this sentence, it turns out that the burden of refuting the arguments of a motion to exclude evidence made by the defense falls on the public prosecutor, regardless of the moment of the statement.

The Plenum of the RF Armed Forces thereby drew the attention of prosecutors to the need to conscientiously fulfill their procedural duties, emphasizing the existence of a problem. However, mere confirmation in the ruling of the well-known and seemingly indisputable rule on the evidentiary presumption is not enough for its implementation in practice.

We have repeatedly witnessed how state prosecutors, in response to reasoned requests from the defense to exclude evidence, responded with lightning speed and simplicity: “The request cannot be granted, since all the evidence was obtained in accordance with the law, and there are no grounds to exclude it,” thereby shifting the responsibility of refuting the arguments of the petition to the court.

Those judges did the right thing who obliged prosecutors to prepare written objections to all arguments in the defense's motion, but such cases were rare.

Unfortunately, the Plenum of the RF Armed Forces did not take advantage of the opportunity to solve a long-standing problem. He could point out that the burden of refuting the arguments of the defense, which is placed on the public prosecutor, is understood as challenging all or the most significant arguments of the petition. In the event that the assigned part 4 of Art. 235 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation, the procedural obligation has not been fulfilled; the court makes a decision in the interests of the party filing the petition.

This would be enough to revive the necessary, but so far only declarative procedural norm, to intensify the activities of public prosecutors, to facilitate the work of judges and thereby organize real competition between the parties when resolving such petitions.

If the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation had conducted statistical research and counted how many cases the defense had filed motions to exclude evidence and how many of them had been granted, then I’m sure we would have gotten a sad result.

Summing up, we have to state that the Plenum of the RF Armed Forces did not create conditions for the practical implementation of the requirements of Part 2 of Art. 50 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation stating that in the administration of justice the use of evidence obtained in violation of federal law is not allowed. Consequently, inadmissible evidence will continue to circulate unimpeded in indictments, corrupting the healthy legal fabric, encouraging law enforcement officers to further violate the rights of citizens and undermining their trust in justice.

Protocols of investigative and judicial actions - classification of evidence

The criminal process considers the records of judicial actions and investigations as independent sources of evidence.

Protocols that certify facts and circumstances are usually established:

- During an investigative experiment, when giving testimony at the scene of a crime.

- During examination, examination, seizure, identification.

- The protocol is the main source of information on the case, on the basis of which the issue of the validity and legality of the court decision is decided.

Thus, it should be noted that a protocol is a written act in which officials, based on direct observation, recorded general information about the facts to be proven.

Personal evidence

Explanations of the parties and third parties about the circumstances of the case are studied by the court along with other evidence. If a party obligated to prove its claims or objections, while having evidence in the case, withholds and does not present them to the court, then the court has the right to draw a conclusion only on the basis of the explanations of the opposite party (Article 68 of the Code of Civil Procedure). Confirmation of the facts in the explanation of the party on which the claim of the other party is based leads to the absence of the need to prove them in the future.

Written explanations must be read aloud during the hearing. The written form of explanations does not make them written evidence. If the court finds that the explanations are untrue and are made:

- under the influence of someone else's will (threats, violence, deception);

- in order to hide the truth;

- as a result of an honest mistake;

then he does not accept them and makes a determination about this.

A witness is a citizen who presumably knows some information about the circumstances of the case being examined by the court. Information provided by a witness, if its source is not disclosed, is not accepted by the court as evidence. Some citizens cannot be witnesses in court (for example, representatives in the process, but only in relation to information that has become known to them in this capacity). The witness is obliged to give truthful testimony under penalty of criminal liability. A number of persons may not testify (this includes close relatives, for example, spouses against each other, as well as some government officials).

Other documents

The classification of evidence in criminal proceedings includes other types of documents collected by legal means in competent institutions and organizations. Such documents set out the facts and circumstances that are significant in the case and related to the immediate subject of proof. Other documents reflect all the circumstances relevant in a criminal case. They are generated not during a criminal event, but in the process of daily activities of institutions and enterprises.

Means of proof

This classification of evidence divides all means of proof into 2 groups:

- personal;

- real (in the broad sense of the word).

In turn, personal means of proof are divided into:

- explanations of the parties and third parties;

- witness statements.

And material (in the broad sense of the word) means of proof are divided into:

- written evidence;

- material (in the narrow sense of the word) evidence;

- audio and video recordings;

- expert opinions.

All of the above means of proof are enshrined in both the Civil Procedure Code (Article 55) and the Arbitration Procedure Code (Article 64). Let us note that in the Civil Procedure Code this list is exhaustive and other means of proof in the process are unacceptable, and in the Arbitration Procedure Code “other materials and documents” are added to the list.

Personal and material evidence

Physical evidence is a material object that reflects the circumstances of a criminal act in the form of any traces of influence. This type can include audio, photo or video recording.

Physical evidence to a lesser extent expresses the traces of a legally significant event that appear in the process of influence.

Personal evidence is the testimony of witnesses, the accused or the victim. This also includes protocols of judicial and investigative actions, expert opinions.

A distinctive feature of this type of evidence is the mental perception of events, as well as the written or oral transmission of information significant in the case.

Written evidence

Written evidence includes:

- contracts;

- acts;

- certificates;

- business correspondence;

- documents of legal proceedings (decisions, sentences, court rulings, minutes of meetings, etc.);

- electronic documents, as well as those received by fax, but they must be certified (for example, by an electronic signature);

- other documents.

For presentation in proceedings, the following rules apply to written evidence:

- they are presented either in the original or in the form of a duly certified copy (only in the original if different copies are contradictory or if this is expressly established by law);

- they can be presented at the meeting via video conferencing (if there are appropriate technical means) (clause 23 of the resolution of the plenum of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation dated February 17, 2011 No. 12);

- a foreign document must be legalized (for some official documents, legalization is not required if this is directly established by an international treaty, but according to Article 255 of the APC, a translation certified by a notary is required).

Direct and indirect evidence

This classification of evidence and its practical significance are also subject to detailed consideration. It is customary to call direct evidence that serves to establish specific circumstances that are subject to further proof. These include the events of the crime, the guilt of the person, and the fact that the crime was committed. Direct evidence may indicate a person’s involvement or non-involvement in a given crime.

Indirect evidence establishes intermediate facts from which a conclusion is drawn about the existence of circumstances to be proven. With their help, it is not the circumstances of the crime themselves that are determined, but only the facts associated with it, the analysis of which makes it possible to find out the availability of the necessary information on the case.

Types of evidence

In legal doctrine, there are 3 classifications of evidence:

- by the type of connection between the evidence and the circumstances of the dispute;

- on the formation process;

- by the source of information about facts (means of proof).

The first classification of evidence divides them into:

- straight;

- indirect.

Direct evidence has a direct connection with the circumstance it defines, while indirect evidence has an indirect connection. But it has a direct connection with the fact related to the circumstance being proven. Such facts are called incidental.

Based on indirect evidence, only a conjectural conclusion about the sought-after circumstance is possible. Therefore, it is believed that with the help of one individual indirect evidence it is impossible to establish the existence of a proven fact (for example, the resolution of the Federal Antimonopoly Service dated 02/03/2012 in case No. A12-11102/07).

In practice, the following rules apply regarding circumstantial evidence:

- they confirm direct ones that lack reliability;

- in the absence of direct evidence, they are used in aggregate (for example, the resolution of the Federal Antimonopoly Service of the Moscow Region dated October 15, 2013 in case No. A40-5132/13);

- such a set must have the property of being systematic; the only possible conclusion about the circumstance being established must follow from it;

- the facts included in the totality must be reliable.

There is more useful information on the topic in ConsultantPlus. If you don't have access to the system yet, you can get it for 2 days for free. Or order the current price list to purchase permanent access.

Primary and derivative evidence

The classification of evidence in criminal proceedings determines its types, such as initial and derivative.

Primary information includes information obtained from a primary source (a witness’s report of the events of a crime that he himself saw and can confirm).

Derivative evidence is information that indirectly reflects the circumstances of the case. In this case, the data obtained will be considered indirect (the witness stated that a crime was committed, which he himself did not see, but was informed about it through a third party).

Concept and properties of evidence. Classification of evidence in criminal proceedings.

Evidence in a criminal case is any information on the basis of which the court, prosecutor, investigator, inquirer, in the manner prescribed by the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Republic of Belarus, establishes the presence or absence of circumstances to be proven in criminal proceedings, as well as other circumstances relevant to the criminal case.

Types of evidence:

a) testimony of the suspect; b) testimony of the accused; c) testimony of the victim; d) witness testimony; e) expert opinion; f) expert testimony; g) expert opinion; h) testimony of a specialist; i) material evidence; j) protocols of investigative actions; k) minutes of court hearings; m) other documents.

In accordance with the rules for assessing evidence, each of the evidence in the case must have the properties of relevance, admissibility and reliability, and all the evidence in the case in the aggregate must also have the property of sufficiency to resolve the criminal case.

Relevance of evidence - connection of the information obtained with the subject of proof:

a) directly establishes the main fact;

b) establishes intermediate facts;

c) establishes the existence of other evidence;

d) characterizes the conditions for the formation of evidence

Admissibility of evidence - compliance of the information received with the requirements of procedural law:

a) proper source;

b) authorized subject;

c) the legality of the method of obtaining evidence;

d) compliance with the rules of recording evidence

Personal come from persons and are expressed in symbolic form. Material are expressed in the physical characteristics of material objects.

The original ones are obtained from primary sources. Derivatives are obtained from intermediate sources.

Evidence of the commission of a crime by the accused, his guilt or circumstances aggravating the responsibility of the accused is incriminating; and evidence that refutes the accusation, indicates the absence of corpus delicti, or the non-involvement of the accused in the crime, or mitigates his responsibility - acquittal.

Direct evidence indicates that a person has committed a crime or excludes his involvement in it. A number of authors consider “direct” evidence that points to any of the circumstances included in the subject of proof. Circumstantial evidence contains information about the facts that preceded, accompanied or followed the event being established and, based on the totality of which, it is possible to conclude whether a crime occurred, whether the accused is guilty or innocent.

Appealing the actions and decisions of the inquiry body, investigator, prosecutor. Order, deadlines. What is the essence of the legal consequences of the practical operation of the principle of the presumption of innocence. Appeal and protest of criminal procedural decisions in criminal proceedings.

In the Law of the Republic of Belarus “On Citizens' Appeals,” a complaint is understood as a requirement to restore the rights, freedoms and (or) legitimate interests of a citizen (citizens) violated by the actions (inaction) of officials of state bodies, other organizations or citizens.

Taking this definition as a basis, a complaint in criminal proceedings can be defined as an appeal to the body specified in the law in oral or written form by a participant in a criminal trial, another person about the violation of his or the person he represents by the body conducting the criminal trial, and a demand for eliminating these violations.

Part 1 art. 139 of the Code of Criminal Procedure provides that complaints from persons specified in Art. 138 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the actions and decisions of the inquiry body, the inquiry officer and the investigator are submitted to the prosecutor who supervises the implementation of laws during the preliminary investigation. Complaints about the actions and decisions of the prosecutor are submitted to a higher prosecutor, and complaints about the actions and decisions of the court are submitted to a higher court.

The prosecutor’s duty to consider complaints against the actions of the preliminary investigation bodies also follows from paragraph 10 of Part 5 of Art. 34 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which prescribes the prosecutor to exercise supervision over compliance with the law, as well as procedural guidance and resolution of complaints against the actions of a subordinate prosecutor, as well as an investigator, an inquiry agency and an inquiry officer during the preliminary investigation and inquiry.

If a complaint against the actions of an official of a criminal investigative body or court is sent personally to this person, he is obliged to forward the complaint to the relevant prosecutor within 24 hours.

In addition, the Code of Criminal Procedure established the right of participants in criminal proceedings to appeal a number of decisions of investigative bodies and the prosecutor in court. These also include a decision to refuse to initiate a criminal case (Part 2 of Article 139 of the Code of Criminal Procedure).

The Code of Criminal Procedure does not establish any specific form of complaint. It can be either written or oral (Part 5 of Article 139 of the Code of Criminal Procedure). A written complaint is drawn up arbitrarily, but it must indicate for which criminal case, what actions (inaction) are being appealed, legal facts and other circumstances indicating the illegality or unfoundedness of the action (inaction), and on what basis the participant in the process filing the complaint, considers the actions taken in relation to him or the decisions taken to be unfounded or illegal.

An oral complaint is usually submitted directly during a procedural action and is entered into the protocol of this action, which is signed by the applicant and the person who accepted the complaint. Oral complaints are usually received directly during one or another investigative action. The investigator or inquiry officer who carried out this action and accepted the complaint cannot consider it, since it is directed specifically at their actions, and are obliged to report it to the relevant prosecutor. However, the procedure for this message is not regulated by law.

The right to appeal procedural actions and decisions taken by the body conducting criminal proceedings arises from the moment these actions are committed. In accordance with Part 1 of Art. 140 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, they can be filed during the entire period of the investigation or trial. At the same time, this norm limits the filing of complaints about the refusal to initiate a criminal case, the termination of preliminary prosecution or criminal prosecution by the statute of limitations for bringing to criminal responsibility. It follows that the decision to terminate criminal prosecution or proceedings in a criminal case, to refuse to initiate a criminal case on such grounds as the expiration of the statute of limitations for bringing to criminal responsibility (clause 3, part 1, article 29 of the Code of Criminal Procedure), cannot be appealed because the appeal period has expired, which to a certain extent limits the rights of the relevant participants in the process.

The body of inquiry, the inquiry officer, the investigator, the prosecutor whose actions are being appealed, as well as the prosecutor considering the complaint, have the right to suspend the execution of the contested decision, with the exception of complaints about detention, detention, house arrest, extension of the period of detention and house arrest, as well as for compulsory placement in a psychiatric (psychoneurological) institution. The decision to suspend is made if there is evidence indicating that the action being appealed is clearly illegal.

The prosecutor or judge who received the complaint is obliged to consider it within 10 days and notify the applicant of the decision made.

Complaints about the refusal to initiate criminal proceedings are sent to the court at the place of investigation of the crime and are considered by a single judge with the participation of the prosecutor. A suspect, a defender, a legal representative, a victim, a civil plaintiff, a civil defendant or their representatives, as well as a person or representative of a state body, enterprise, institution, organization, association, based on whose statements a criminal case was initiated or denied, may take part in the court hearing. initiation of a criminal case.

Having considered the complaint, the judge makes a reasoned decision (Part 5 of Article 142 of the Code of Criminal Procedure): 1) to satisfy the complaint and cancel the decision to refuse to initiate a criminal case; 2) about leaving the complaint without satisfaction. These decisions come into force immediately, but can be appealed by the above-mentioned persons.

The judge’s decision to cancel the decision to refuse to initiate a criminal case is sent in accordance with Part 5 of Art. 142 of the Code of Criminal Procedure to the head of the relevant criminal prosecution body to conduct an additional check on the materials.

Accusatory and exculpatory evidence

Incriminating evidence refers to facts that establish a person’s guilt in an act committed. This type of data includes the testimony of the accused who admitted his guilt, the testimony of the victim or witness. A characteristic feature of incriminating evidence is the aggravation of the criminal’s guilt.

Exculpatory evidence is information that disproves a person’s guilt. Such circumstances include the testimony of persons participating in the case regarding the innocence or non-involvement of the subject in the crime committed. A characteristic feature of this type is considered to be mitigating circumstances.

Criminal law, civil law

Page 1 of 5

The division of evidence into direct and indirect is based on their relationship to the circumstances being established. Direct evidence indicates the fact being proven directly, directly, in one step. The content of direct evidence is the fact being proven. For example, an eyewitness talks about the circumstances of a crime he observed. His testimony directly points to the events he describes. Direct evidence is a direct observation of a fact (or, as they used to say, a direct observation of the truth). Indirect evidence indicates the fact being proven not directly, not directly, but indirectly. It points to some other fact, which in itself has no legal significance, but through a certain series of conclusions arising from it, indirect evidence allows us to confirm the sought fact. If a witness describes not the crime itself, but its consequences, for example, he saw the suspect leaving (or running away) from the scene of the crime, from this a conclusion can be drawn about the possibility of him committing a crime.

At the same time, this witness directly indicates the fact that the suspect was removed from the scene of the crime, therefore, in relation to this fact, his testimony is direct evidence. Thus, any evidence is both direct and indirect at the same time. Directly pointing to some intermediate fact, the proof is at the same time indirect in relation to the main fact, which can be established with the help of this intermediate fact through a series of consistent conclusions.

For example, testimony establishes a quarrel based on jealousy between spouses. The testimony of a witness is direct evidence of a quarrel, from which a conclusion can be drawn about the presence of a motive to commit murder. The presence of a quarrel is indirect evidence of jealousy, jealousy is indirect evidence that the jealous person has committed murder.

The classification of criminal procedural evidence into direct and indirect, thus, depends on what we take as the starting point, i.e. for the basis of classification. However, no consensus has been developed on the basis of this classification in the theory of criminal proceedings. Some scientists believe that the basis of classification is the relation of evidence to the subject of proof, while others believe that it is to the main fact. Based on the concept of the burden of proof formulated in Art. 14 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, it can be considered that the subject of proof in a criminal case is the guilt of a person in committing a crime. A person’s guilt can be established in different ways depending on the content of the evidence supporting it. Direct evidence links a specific person to the commission of a crime. Indirect evidence connects a person not with the fact of committing a crime, but with some other (intermediate) fact from which it can be concluded that the accused committed a crime [1]. If we take the main fact as the basis for classification, understood only as the fact that a person has committed a crime, it should be recognized that a significant part of the evidence is indirect in nature or does not lend itself to such classification at all, and is beyond the division of evidence into direct and indirect [2].

It is unlikely that such an approach to classifying evidence can be considered justified. Since the main fact is not the entire set of circumstances subject to proof, but only a part of them, the classification basis under consideration does not correspond to one of the conditions of any scientific classification, since it does not cover all classified phenomena.

On the other hand, the main fact does not consist of any one fact; it includes, as we have seen, many facts that in their totality form the corpus delicti. How to consider evidence that directly establishes the place or time of a crime? [3] Can there be such evidence that can directly and directly establish the entire corpus delicti? Reflection on these questions leads to the conclusion that neither the subject of proof nor its main fact can be taken as the basis for dividing evidence into direct and indirect. Such a basis is the relation of the evidence to each specific, individual fact that can be proven or, in the language of logic, to the thesis being proven.

The division of evidence into direct and indirect is due to the existence of different ways to establish certain circumstances. In general, it can be argued that the path of direct evidence is simpler and shorter than the path of indirect evidence. The connection between direct evidence and the subject of proof is obvious, it is simple and does not require additional justification. “The objective connection of such facts with the subject of proof is a connection between the part and the whole... Here the task comes down only to establishing the reliability of information about this fact,” writes one of the main researchers of indirect evidence, A. A. Khmyrov [4]. The content of direct evidence is information about the circumstance to be proven [5].

- Forward